- What is Organisation Design?

- Introducing the Organisation Evolution Framework

- Consistency and Intentional Design. Building the Organisation of the Future.

- Building the Intentional Organisation

- Business Models: the theory and practice

- Strategy Frameworks: The Theory and the Practice

- Organisation Models: a Reasoned List between Old and New

- Operating Models: the theory and the practice.

- Leadership Models: The Theory and the Practice

- Purpose: The Theory and the Practice

- Corporate Culture: The Theory and the Practice

- Organisation Ecosystem: The Theory and the Practice

Corporate Culture is the seventh component of the Organisation Evolution Framework. It’s the second of the “soft” elements after Leadership, and probably one of the most difficult to define. The concept itself of Culture is a concept that triggers many discussions among different social scientists on precisely what it is, how it is defined, how it forms, how it evolves, and what it truly means for individuals. When we apply this concept to organisations, we trigger even bigger quarrels on its exact meaning, despite the many activities done in the name of culture change.

As with the previous articles of this series, I will try to represent the existing complexity of the topic, once again showing that it is impossible to find a correct answer. The key lesson, as with the previous issues of Leadership, is that we need to find consistency in what this topic means, in the framework of our Intentional Design effort.

Defining Organisational Culture

Similarly to some other components of Organisation Design, the concept of Organisational Culture (often used with its synonym of Corporate Culture) developed around the 1960s and has since steadily be used in management literature, as can be seen in the Google ngram below.

As mentioned, there are many different definitions of Organisational Culture; perhaps the most known one is “the way we do things around here” (Lundy and Cowling, 1996). In a way, many of the definitions have been focused on identifying and listing the key components and elements of organisations cultures. For example, it is widely accepted that organisational Culture is defined as the deeply rooted values and beliefs that are shared by personnel in an organisation (Sun, 2009).

Many elements can be included on the definition: organisation’s expectations, experiences, philosophy, as well as the values that guide member behaviour and is expressed in member self-image, inner workings, interactions with the outside world, and future expectations. Culture is based on shared attitudes, beliefs, customs, and written and unwritten rules that have been developed over time and are considered valid but the organisation’s members. Culture also includes the organisation’s vision, values, norms, systems, symbols, language, assumptions, beliefs, and habits (Needle, 2004).

In business terms, other phrases are often used interchangeably, including “corporate culture,” “workplace culture,” and “business culture.” (Cancialosi, 2017)

When we check the concept of Organisational Culture, there are various points of view we need to take into consideration. Maull, Brown and Cliffe have proposed (2001) a framework of reference to analyse Organisational Culture theories that I find useful, and that I will follow with a few updates.

The first point to consider is rather philosophical and asks whether organisational Culture is an independent or dependent (internal) variable. The second instance looks instead at the themes that the various authors and researchers in the field have followed.

Culture As An Independent Variable

This view essentially looks at Organisational Culture as something that is “imported” into the organisation through membership. This view takes as its key premise there are specific characteristics of “good” cultures that are universal and easily imported into the organisation (Maull, Brown and Cliffe, 2001).

In this view, Culture is seen as something an organisation has.

As such Culture can be crafted into something “positive” for the organisation, through specific change initiatives. Several management theories look at the role of managers in creating effective corporate cultures that support corporate strategy. This is, for example, the view of Stanley Davies in his 1984 book Managing Corporate Cultures. A belief that is shared by another approach widely spread in the eighties the Theory Z of Organisation (Ouchi, 1981) which proposed an essentially cultural approach to the creation of successful organisations.

The crucial assumption here is that Culture is an objective and tangible phenomenon which can be changed through the application of direct intervention methods (Maull, Brown and Cliffe, 2001). Many research and experiments went in this direction, and there is substantial literature that looks at national cultural elements, trying to identify their impact on organisations. Many tools have been developed in this respect, and some of the models we will see below (Hofstede and Trompenaars, for example) are firmly based on this point of view.

Culture As A Dependent Variable

This view essentially states that organisations themselves are Culture producing phenomena. From this point of view organisations are seen as social instruments that produce goods and services, and, as by-product, they also produce distinctive cultural artifacts such as rituals, legends and ceremonies (Smircich, 1983). As such each organisation develops a unique culture which is the product of its history, its development and the present situation.

In this view, Culture is something an organisation is.

Adopting this perspective means building the culture concept within a systems theory framework which holds that the organisations exist largely in a determined relationship with its environment (Maull, Brown and Cliffe, 2001). It becomes the glue that holds things together, a strong culture being the element that creates the appropriate balance and effectiveness to the organisation (Deal and Kennedy, 1982).

This line of thought makes intervention on Culture more complicated, but no less desirable. Mainly because the resulting understanding is that firms that have cultures supportive of strategy are likely to be successful, while firms that have insufficient “fit” between strategy and Culture must change since it is the Culture which supports the strategy.

In practical terms, this approach sees activities as how to mould and shape internal Culture in particular ways and how to change Culture, consistent with managerial purposes (Smircich, 1983).

Key Themes of Organisational Culture

The same Maull, Brown and Cliffe (2001) also have listed four main themes they identified in organisational culture literature. Let’s see them together, as this classification is useful to establish a typology of the existing frameworks.

Culture as a Learnt Entity

This theme looks at learning as a critical component in organisational Culture. As such, the focus is on “the way we do things here” or “the way we think about things around here” (Williams, Dobson and Walters, 1996). In general, these definitions focus on the way we act and the way we think. In this regard, a widely accepted definition fo culture is that of Schein:

“The pattern of basic assumptions that a given group has invented, discovered, or developed in learning to cope with its problems of external adaption and internal integration, and that have worked well enough to be considered valid, and, therefore to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems.” (Schein, 1984)

We will see more in detail Schein’s view later on in this article. What is essential is to understand the effects of this approach: Culture is taught to new members as a way of behaving that is “correct” for the specific organisation. In this sense, Culture becomes a self-perpetuating feature for organisational survival and growth. Also, a consequence of this view is that the visible artefacts of Culture are distilled down to the behaviours that people teach to others as they join the organisation.

In other cases, we see Organisational Culture defined as the right way in which things are done or problems should be understood in the organisation (Sun, 2009).

This point of view has had a significant impact on a lot of HR initiatives, particularly around the importance of induction and onboarding programmes. When Culture needs to change, this idea acts at the level of changes to individual and team behaviours, often by reconstructing narratives through ad-hoc storytelling.

Culture as a Belief System

This theme looks at the impact of beliefs in the definition of Culture, as an extension of the management models that characterise the organisation. A description that is linked to this theme comes from Davis:

“The pattern of shared beliefs and values that give members of an institution meaning, and provide them with the rules for behaviour in their organisation.” (Davis, 1984)

Thinking in terms of beliefs system means distinguishing between different types of beliefs. Some are profound, guiding thoughts that impact the actions of the entire organisation. Difficult to change, they can be inferred from artefacts and behaviours of members. But there is also a second category of beliefs, sometimes called “daily beliefs”. These can be described as the rules and feelings about everyday behaviour. However these are dynamic and situational, they change to match context. Under this set of definitions, organisational Culture is a set of shared assumptions that guide what happens in organisations by defining appropriate behaviour for various situations (Ravasi and Schultz, 2006)

Seen this way, it is understandable how Organizational Culture affects the way people and groups interact with each other, with clients, and with stakeholders. Also, organisational Culture may influence how much employees identify with their organisation (Schrodt, 2002).

A consequence of this theme is that as you build an organisation from scratch, you should define the two-three core principles on which to establish foundational beliefs. An example can be Creativity in the case of Pixar, as we have seen in the book by Ed Catmull, a great example of intentional design. Actions that go against the core beliefs will most probably fail unless they are accompanied by an extensive program to support the modification of these beliefs.

Culture as Strategy

Culture eats strategy for breakfast is one of the most famous quotes, often attributed to Peter Drucker. Whoever originated that quote, is an excellent frame for those that think of primacy of Culture vs strategy, or an intimate relationship between the two. Paul Bate goes at length in explaining his point of view that Culture and strategy are the same things.

“I am not suggesting that Culture is like strategy (and vice versa), nor am I saying that Culture and strategy are closely related… What I am saying is that one is the other… Culture is a strategic phenomenon: strategy is a culture phenomenon.” (Bate, 1995)

The implication of this theme is a strong focus on strategy development as a cultural activity. The basic assumption is that beliefs impact the definition of strategy. Which is why the definition of a strategy needs to take into consideration the cultural aspects, and need to have a storytelling component. Many of the activities that related to the usage of Purpose as a Strategic Asset have their foundation onto this theme.

The second consequence of this theme is that Culture Change is Strategic Change. The idea to set up a process that is separate is simply flawed and constitutes a waste of energy.

On one side, this theme seems to deliver an even more pivotal role to Culture, on the other side, it ends up discouraging specific interventions in the domain.

Culture as Mental Programming

A fourth theme, which integrates some of the other views partially, sees Culture as a “mental programming” of individuals. One of the key promoters of this view is Hofstede (1980) who defined Culture as the “collective programming of the mind, which distinguishes the members of one category of people from another.”

This definition stresses that Culture:

- Is collective and not a characteristic of individuals (shared values)

- Is mental “software”, therefore invisible and intangible as such

- Is attractive only to the extent that it differentiates between categories of people.

We’ll see Hofstede’s work more in detail below, but what is essential is that Hofstede tried to develop a cultural typology of the relationship between national cultures and organisational cultures. In this view, Culture is valid only if it can be measured, thus the focus that Hofstede had on the development of surveys and measurement tools. A similar approach has been created by Fons Trompenaars, also looking at national cultures.

This theme makes Culture more a “Measurable element”, but more challenging to change, as the influence of local conditions and national cultures is a lot more impactful than any element that can be defined by the organisation itself.

Common Characteristics

All the themes have something in common: the idea that several deeply rooted assumptions influence the behaviours of the members of an organisation. This is why Culture is often described using the Iceberg Metaphor, by which it is underlined that there is a large number of component that are not visible but influence the visible “tip of the iceberg”. This metaphor was first proposed in 1976 by E.T. Hall, and despite some critiques, it still is an excellent illustration of a complex concept.

Later on, I will propose my working definition of Culture. I want, however, to dedicate some time to the definitions and models that are more used in organisational contexts, trying to review how these also impact change management programs in the organisation. In my view, Organisational Culture is never a static component, but rather a dynamic element that continually evolves, often slowly, sometimes faster.

Culture Frameworks applied in Organisations

Through this section, I will investigate a number of different Culture Frameworks that are used and applied within the organisation to either try to understand existing cultures or to define culture change programs aimed at impacting the organisation effectiveness.

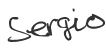

Competing Values Framework

Robert E. Quinn and John Rohrbaugh developed the Competing Values Framework as they searched for criteria that predict if an organisation performs effectively (Quinn and Rohrbaugh, 1983). Their empirical studies identified two dimensions that enabled them to classify various organisations’ “theory of effectiveness” (Goldminz, 2020).

The first dimension analysed, is Flexible vs Focused. It looks at how organisations are differentiated based on an emphasis on flexibility, dynamics or preferably from an emphasis on stability, order and control.

The second dimension is Internal vs External. It differentiates internal orientation with a focus on integration, collaboration and unity vs an external exposure with a focus on differentiation and competition.

These dimensions form four quadrants, each representing an ideal-type of organisation and individual behaviours.

1.Hierarchy

Hierarchies arise and are useful when organisations are inward-looking and focused on stability and control. With these values, organisations look within themselves to drive control and efficiency. Hierarchies bring structure and rigour to operations though controlled operating processes. They also ensure that things are done in smooth, ordered and controlled ways.

These organisations may be less responsive to changing situations and the demands of the market than other organisations.

2. Clan

Clans arise when organisation are primarily inward-looking and value responsiveness. With this value mix organisations look within themselves for ways to respond quickly and effectively to change. Clans value teamwork and collaboration. They also often feel like families that are glued together by their desire to work towards their common goals.

These organisations may be more focused on and interested in their internal outcomes, such as engagement, than in external outcomes, such as customer results. If there is a conflict between the needs of the customer and the needs of the organisation, the organisation will probably win, provided the need isn’t a matter of survival.

3. Adhocracy

Adhocracies exist where organisations are outward-looking and focused on being flexible and responsive. With this value mix organisations value pace of work, innovation and risk-taking, all in the name of moving quickly to meet external needs.

These organisations are held together by their desire to experiment, innovate and create quickly. As a result, they are entrepreneurial, ad-hoc, and driven to create new things and find new ways of succeeding.

While these organisations may grow and develop quickly, they may have less control over their operations and provide less nurturing environments than other organisations.

4. Market

Market organisations are outwards looking and internally focused. They are very aware of the organisation’s position in the market and are driven to improve it. As a result, they are highly customer and supplier focused and prioritise doing an excellent job for customers and improving market position.

These organisations are often competitive. They bond through their desire to get things done and to win in the current marketplace. As a result, they may be less forward-looking and responsive than some organisations and may be less nurturing than the same organisations.

Culture Canvas

Following the practical usage of other toolkits in the form of canvases, also Culture got its approach into this way. There are at least four different types of Culture Canvas available, and I’m listing them here in an individual section only for ease of reach.

The People, Actions, Results Culture Canvas developed in The Netherlands by Kevin Wejers and dY/dX. It is described as an “open framework” to make Culture actionable.

The tool is meant to be used both at the team or at an organisational level and loosely refers to the components of Schein’s model.

The tool, however, mixes a few concepts that are not customarily attributed necessarily to Culture, like Key Performance Indicators, and becomes more of a strategising planning tool than a specific culture focused actionable framework.

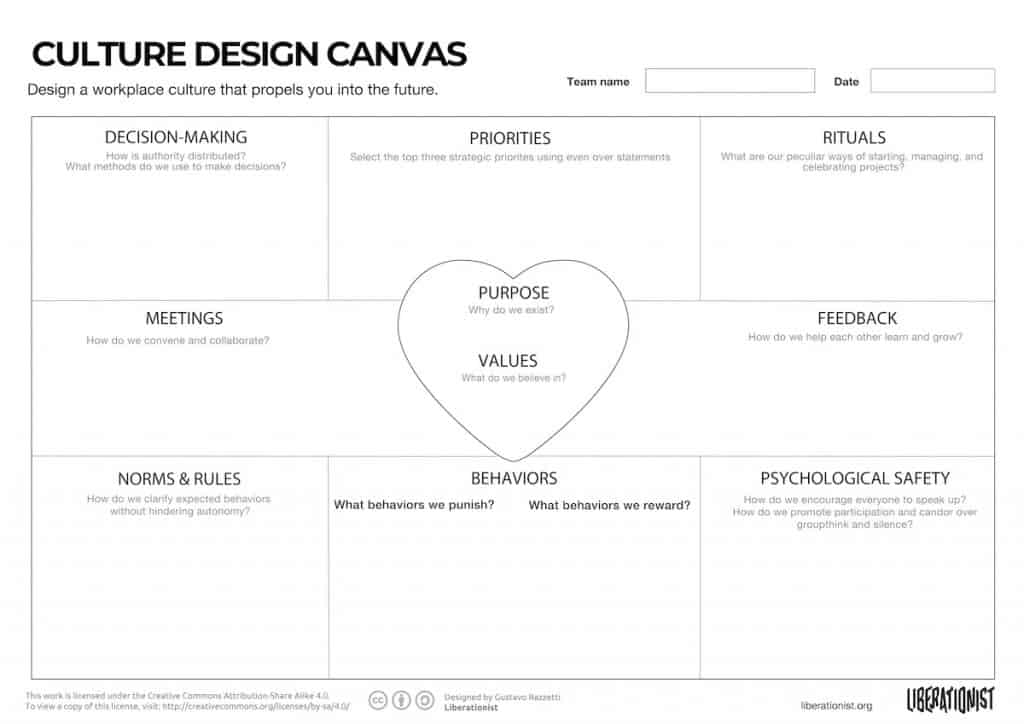

The Culture Design Canvasrealised by Gustavo Rizzetti is “a strategic tool for mapping, visualising, designing, and evolving your company culture.”

The tool allows mapping both the current Culture (AS-IS), but also future state culture, thus allowing to develop a “fit-gap” analysis and a plan of action.

Interesting to notice a few elements derived from recent research, such as Psychological Safety. Gustavo Rizzetti has created several canvases available for a few successful companies with what he identifies as strong cultures, such as Pixar, Netflix, Patagonia, Spotify.

The Culture Canvas is instead a tool developed by Marc Vollebregt, also loosely based on Schein’s Framework and the Operating System Canvas.

The tool tries to represent Culture becomes as easy as filling in a piece of paper – easy to understand for everyone, concrete to work with, and tangible to change.

I doubt that Culture can be indeed reduced to filling up a sheet of paper, and also find it a bot naif the idea that everything can be reduced to a single workshop and one tool only.

I believe more breadth and depth of investigation is required-

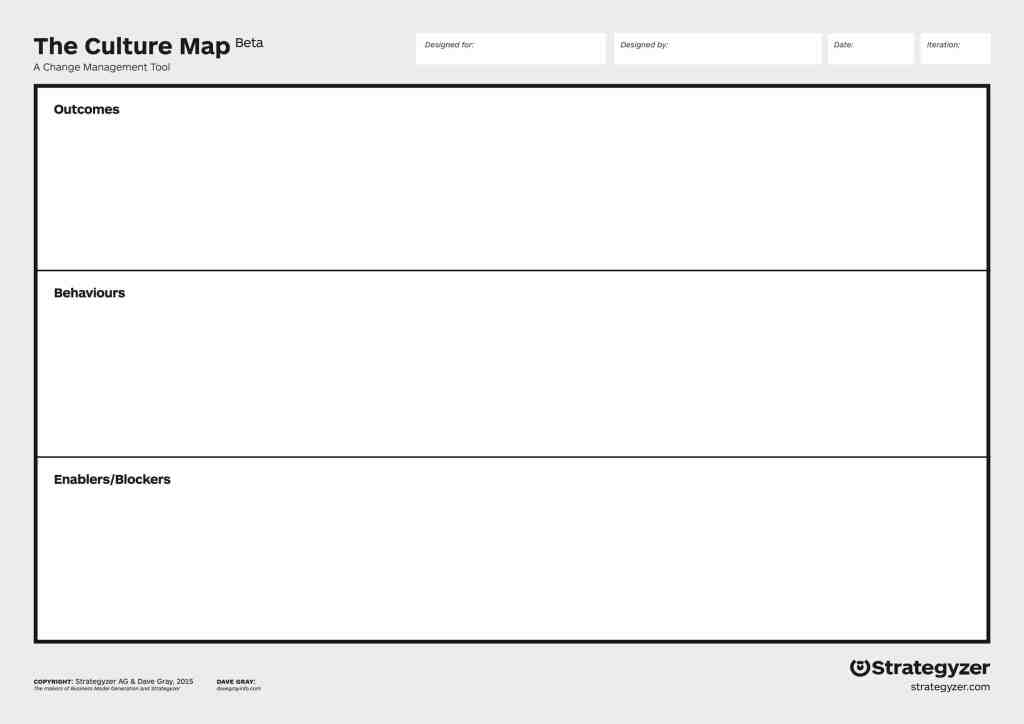

Last we have the Culture Map developed by Dave Gray and proposed by Strategyzer as part of their toolkit.

The idea is that it is a “tool that focuses on employee development”. It is pretty simple in this structure, focusing on behaviours (either current or desired), outcomes and mapping of enablers and blockers.

The big absent in this canvas is Values and Purpose. This is by design, as the authors wanted to focus on elements that are in control of the team that promote change within the organisation and ideally design and prototype their organisation culture.

The Culture 500 Project

Several authors have been trying to find a way to compare and benchmark cultures across industries, countries and sectors. An exciting project in this regard is that developed by MIT Sloan Review and CultureX, and that uses Glassdoor data to assess the Culture of 500 companies based on several values. Following the slogan Culture Matters. Now we can measure it (Sull, Sull and Chamberlain, 2019) this project provides a promising framework based on the exploitation of Machine Learning Technologies. This exploits the high number of reviews that Glassdoor collected since its launch in 2008: more than 49 million reviews and employee insights, covering approximately 900,000 organisations. The toolkit elaborated checks the free text reviews that employees fill in, not just the ratings used.

The project follows the definition of Culture as a set of norms and values that are widely shared and strongly held throughout the organisation (O’Reilly and Chatman, 1996). The researchers listed the most common values reported by organisations and chose what they have defined as The Big Nine.

For each of the Big Nine, we calculate the percentage of each company’s Glassdoor reviews that mention the value (incidence) as well as the rate of reviews that discuss the value in positive terms (sentiment).

An online Culture 500 interactive tool provides users with a snapshot of how frequently and positively employees within a company talk about the Big Nine values, allowing to review both individual organisations as well as compare entire industries.

I find this tool extremely useful to assess the impact of cultural actions inside an organisation. True, external reviews might be skewed to a more pessimistic vibe, but internal surveys might have the contrary effect after all. The value of seeing a comparison in a domain that is generally limited to financial numbers has its merit. It can help evaluate, for example, the impact of specific measures on the perceived Culture. For the moment the project has been running for two years, but it will be interesting to see once some data points are present across an arc of time sufficiently long to assess the value of specific actions.

Cummings & Worley Guidelines for Culture Change

A well-known framework for Culture Change is that proposed by Cummings & Worley (2004), made up of Six Guidelines for Culture Change. This framework is heavily built on the concept of “leading by examples”, and shows a full strategic involvement of the organisation leadership team. It also aligns with many of the Change Management tools we have seen already.

- Formulate a clear strategic vision.

To make a cultural change effective, a clear vision of the firm’s new strategy, shared values and behaviours are needed. This vision provides the intention and direction for the culture change and needs to be transparent in all its directional aspects. - Display Top-management commitment.

It is essential to keep in mind that culture change must be led from the top of the organisation, as the willingness to change of the entire senior management is a crucial element to allow emulation by the rest of the organisation. - Model culture change at the highest level.

The change should not only be led by the top but also modelled by its actions. It is essential to note this aspect, as a simple push down communication message of change will not be sufficient. The behaviour of the top management needs to symbolise the kinds of values and behaviours that are part of the new Culture the company wants to implement. This will also help in managing the gap between the as-is and the to-be, as it will be possible for the teams to assess the difficulty in changing or adapting behaviours to the new reality. - Modify the organisation to support organisational change.

Now it’s time to change the organisation so that it can support change. The authors essentially consider the evolution of Culture as having a natural impact on the organisation set-up as well. - Select and socialise newcomers and terminate deviants.

A way to consolidate a change in Culture is to connect it to the organisational membership; people should be selected and terminated, if needed, in terms of their fit with the new Culture. - Develop ethical and legal sensitivity

Changes in Culture can lead to tensions between organisational and individual interests, which can result in ethical and legal problems for organisations. For example, many changes might affect employee integrity, control, equitable treatment and job security. It is therefore essential to consider the ethical and legal aspects around this and plan them in the change process.

Although this approach can be applied to a variety of different definitions of cultures, I have listed it here because this model is widely accepted. I want, however, to underline the top-down message, these guidelines suggest, especially with the idea of removing deviant, which at first may seem a drastic action. However, depending on the depth of change, often culture changes produce an ejection (voluntary for the most part) of individuals that don’t fit the new Culture anymore.

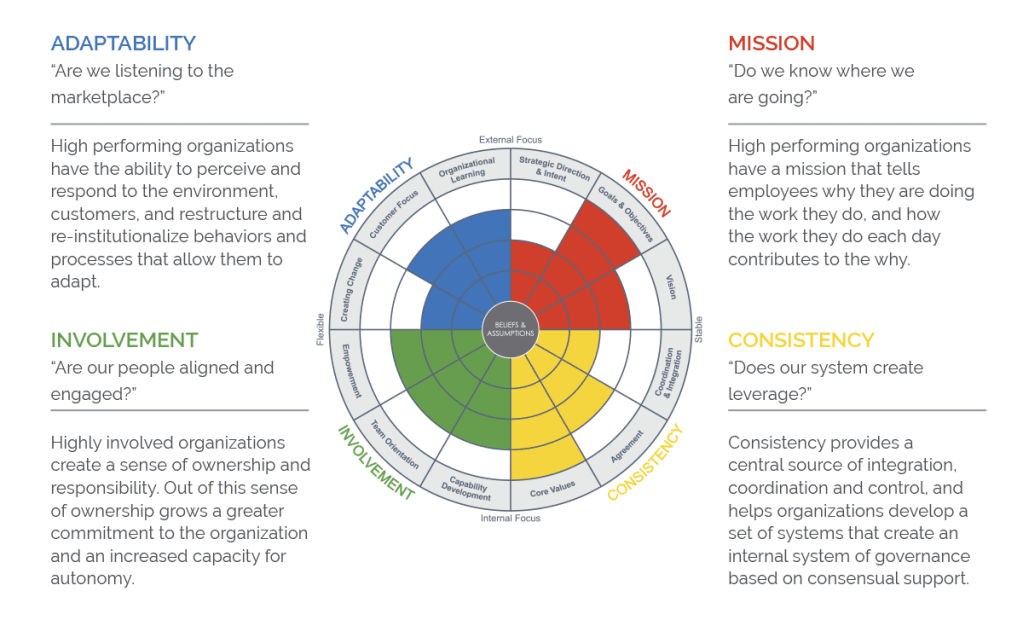

Denison Organisational Culture Model

The Denison Organisation Culture Model (Denison, 2012) has been developed based on the Competing Values Framework, with a focus on establishing a measurable toolkit, by Daniel Denison and his consulting firm. Their work is based on the Denison Organizational Culture Survey (DOCS) to assess a company’s current strengths and weaknesses as they apply to organisational performance. The survey measures four key cultural traits and twelve related management practices.

The model assesses strengths in four key areas of your corporate culture: Adaptability, Mission, Involvement, and Consistency.

- Mission. Do you know where you’re going? Do you have clear goals and a strategy to reach them?

- Adaptability. Are you listening to the marketplace to customers? How well do you identify and respond to their changing needs?

- Involvement. How well do you empower employees, build teams, and develop the human capability in your organisation?

- Consistency. Have you established coordinated systems that enable you to build agreement based on your core values?

The foundation of a diagnostic tool makes this a standard toolkit to be used to assess the current status. Applying a typical “to-be” scenario development, it is also possible to establish the trajectory for a change programme, understanding the gaps that are easier to be filled in.

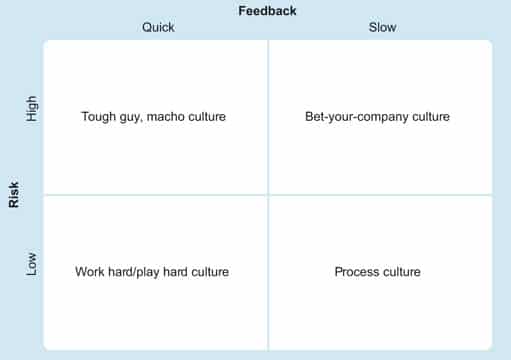

Deal and Kennedy model of organisational culture

According to Deal and Kennedy’s (1982), the most significant single influence on a company’s Culture is the business environment in which it operated. They called this ‘corporate culture’, which they asserted embodied what was required to succeed in that environment. This could be analysed by looking at two dimensions: the degree of risk associated with the company’s activities, and the speed at which companies – and their employees – get feedback on whether decisions or strategies are successful.

By feedback Deal and Kennedy did not mean just bonuses, promotions and informal feedback. They use the term much more broadly to refer to knowledge of results. In this sense, a goalkeeper gets instant feedback from making a great save. Still, a surgeon may not know for several days whether an operation is booming, and it may take months or even years to discover whether a decision about a new product is correct. (OpenLearn, 2019)

Deal and Kennedy distinguish between quick and slow feedback and distinguished Risk between High and Low. This way, they have obtained a four-quadrant model with four types of cultures, here described in the words of the authors.

- The tough guy, macho Culture

A world of individualists who regularly take high risks and get quick feedback on whether their actions were right or wrong. - The work hard/play hard Culture.

Fun and action are the rules here, and employees take few risks, all with quick feedback; to succeed, the Culture encourages them to maintain a high level of relatively low-risk activity. - The bet-your-company Culture

Cultures with big-stakes decisions, where years pass before employees know whether decisions have paid off. A high-risk, slow-feedback environment. - The process Culture

A world of little or no feedback where employees find it hard to measure what they do; instead, they concentrate on how it’s done. We have another name for this Culture when the processes get out of control – bureaucracy!

The authors themselves agree that this model is simplistic, but it can be a useful starting point for looking at your organisation. Often a mix of all four cultures may be found within a single organisation. Furthermore, they suggest that companies with strong cultures will skilfully blend the best elements of all four types in a way that allows them to remain responsive to a changing environment. This way, the model can also support a culture change transition, by intentionally looking at two dimensions that we are seeing are common even in other models: Feedback and Risk

Handy Model of Organisational Culture

Charles Handy has been a prolific writer on the topic of Management and the importance of Culture. He also developed a model based on four specific types of cultures, each based on four characteristics Classes of Culture. The idea is that civilisations can be organised as focused on Power, Roles, Task or Person. These are made highly visual, in the style of the author, in his book The Gods of Management, and associated with four greek mythology deities.

- Zeus – The Club Culture (Power)

Zeus presides over a highly centralised ‘Club’ Culture, where one dominant executive holds all the reigns of power, making all of the important decisions themselves. They control all the essential resources and can have low acceptance of what they perceive as under-performance. This Culture tends to arise under a dominant and successful founder, or with the ascendancy of a charismatic leader. Political parties, start-ups, and crime families often share this Culture. - Apollo – The Roles Culture

Mature, bureaucratic organisations adopt a reliable, stable, rule-based culture, where everyone has a specific role. People know what is expected of them and will rarely step beyond those boundaries. Reporting lines are well-defined, and decisions follow set procedures. Job positions confer authority to make those decisions, and processes can be long-winded and inflexible. Apollo cultures struggle to adapt to a changing environment. - Athena – The Task Culture

The Athena culture is a meritocracy, where the ability to think and get things done is highly valued, and rewarded well. Talent is well rewarded, and teams are fluid, with people coming together to work on projects and solve problems. Authority is less critical here than knowledge, expertise and the ability to influence and persuade. You can see this Culture in consultancies, research organisations, and in agile business units of larger, forward-thinking businesses that may be stuck with an Apollo or Zeus culture. - Dionysus – The Existential Culture (People)

The Dionysus culture is all about me, me, me. It serves the individuals and can lead to both creative freedom and equally internal discord and unproductive competition. The organisation is little more than the home and resource for a set of self-motivated individuals who often care more about their position than that of the organisation. Accounting and law firms are good examples because of the partnership nature of the businesses. So too are pressure groups.

The model is probably not widely applied anymore, but Handy’s intuition is genuinely valid on the relationship between Culture and organisational elements. As we have seen previously, he also envisaged new forms of organisational structures, anticipating trends towards self-management and self-organisation.

Hofstede Model of Organisational Culture

Geert Hofstede is a world-known expert in Culture, as he has been one of the first scholars to investigate national cultures, developing a model that identified several components in the so-called six dimension model (Hofstede, 1985).

- Power Distance (PDI) – which indicates to the extent to which less powerful members of a society accept that power is distributed unequally.

- Individualism versus Collectivism (IDV) – which means the level at which individuals look after themselves or their immediate families, or instead consider themselves a part of “larger groups”.

- Masculinity versus Femininity (MAS) – is not about gender, but rather about dominant values expressed: achievement, performance, status in masculine societies, cooperation, people-orientation and consensus for the feminine societies.

- Uncertainty Avoidance (UAI) – refers to the extent to which people feel threatened by uncertainty and unpredictability and try to avoid these situations.

- Long-Term versus Short-Term Orientation (LTO) – refers to the extent to which a society exhibits a future-oriented perspective rather than a near-term point of view.

- Indulgence versus Restraint (IVR) – refers to the level of relatively free gratification that some societies allow vs other where strict social norms regulate gratification.

As such, he has been able to classify countries across these dimensions, developing a toolkit that also allows comparison of country ratings for each of the dimensions.

In the nineties, he has further expanded the model also to include the Organisational Culture as an investigation dimension. Mainly through the work at IBM; he analysed the impact that national Cultures have on organisations.

Essentially the idea expanded by Hofstede is that organisational Culture touches upon the outer 3 three layers of the so-called, “culture onion” – working practices exemplified by symbols, heroes and rituals.

This has led to a new model, developed and called Multi-Focus Model on Organisational Culture. It also consists of six dimensions, but they are slightly different (although it is easy to find a logical relationship with the national culture dimension we have seen). Let’s see them in detail.

- Means-Oriented VS Goal-Oriented (Organisational Effectiveness)

This dimension is closely connected to the effectiveness of the organisation. In a means-oriented culture, the critical feature is how work has to be carried out; people identify with the “how”. In a goal-oriented culture, employees are primarily out to achieve specific internal goals or results, even if these involve substantial risks; people identify with the “what”.

In a highly means-oriented culture, people perceive themselves as avoiding risks and making only a little effort in their jobs, while each workday is pretty much the same. However, in a very goal-oriented culture, the employees are primarily out to achieve specific internal goals or results, even if these involve substantial risks. - Internally Driven VS Externally Driven (Customer orientation)

In highly internally driven culture, employees perceive their task towards the outside world as a given, based on the idea that business ethics and honesty matter most and that they know best what is good for the customer and the world at large.

In a very externally driven culture, the only emphasis is on meeting the customer’s requirements; results are most important, and a pragmatic rather than an ethical attitude prevails. - Easygoing Work Discipline VS Strict Work Discipline (Level of Control)

This dimension refers to the amount of internal structuring, control, and discipline. A very easygoing culture reveals an internal fluid structure, a lack of predictability, and little control and discipline; there is a lot of improvisation and surprises. A rigorous work discipline reveals the reverse. People are very cost-conscious, severe and punctual. - Local VS Professional (Focus)

In a local company, employees identify with the boss and/or the unit in which one works. In a professional organisation, the identity of an employee is determined by his profession and/or the content of the job.

In very local culture, employees are very short-term directed, they are internally focused, and there is robust social control to be like everybody else. In a very professional culture, it is the reverse. - Open System VS Closed System (Approachability)

This dimension relates to the accessibility of an organisation. In a very open culture, newcomers are made immediately welcome, one is available both to insiders and outsiders, and it is believed that almost anyone would fit in the organisation. In a very closed organisation, it is the reverse. - Employee-Oriented VS Work-Oriented (Management Philosophy)

This aspect of organisational Culture is most related to management philosophy. In very employee-oriented organisations, members of staff feel that personal problems are taken into account and that the organisation takes responsibility for the welfare of its employees, even if this is at the expense of the work. In very work-oriented organisations, there is heavy pressure to perform the task even if this is at the cost of employees.

There is also another component that is interesting about this model, the fact that it distinguishes four types of organisational Culture:

- Optimal Culture: is the organisational culture that best supports your organisation’s strategy to be successful.

- Actual Culture: is the Culture your organisation or department currently has.

- Perceived Culture: is the culture people in the organisation think it has.

- Ideal Work Environment: which gives valuable information about the preferences of the people working in the organisation.

The diagnostic tools developed aim at capturing all four of these types, an exciting aspect of this methodology, particularly in the distinction between actual and perceived Culture.

Last but not least, Hofstede’s model provides also a great way to illustrate the impact of countrys’ images and mental models in organisations, an element to be considered especially in the management of mulltinational teams and structures.

Johnson and Scholes’ Cultural Web Model

As we have seen, there is a stream of thought that looks at a strong connection between strategy and Culture. Deriving from this concept, there’s the consequent idea that unsuccessful implementations of a strategy can also be linked to a non-effective culture. This led to research in the diagnostic toolkit to assess Culture.

Published by authors and academics in the fields of business, Leadership and management, Kevan Scholes and Gerry Johnson in 1992, the Cultural Web is one of these tools useful for analysing and altering assumptions surrounding the Culture of an organisation. It can be used to highlight specific practices and beliefs and to align them with the strategy subsequently.

Johnson and Scholes identified six distinct but interrelated elements which contribute to what they called the “paradigm” of an organisation, equivalent to what others define as the pattern of the work environment, or the values of the organisation.

They suggested that each may be examined and analysed individually to gain a clearer picture of the broader cultural issues of an organisation. The six contributing elements (with example questions used to explore the organisation at hand) are as follows:

1. Stories and Myths

These are the descriptions of previous events – both accurate and not – which are told by individuals within and outside the company. Which the company remembers events and people indicates what the company values, and what it chooses to remember through storytelling. Some questions can be useful to frame the analysis of this element.

- What form of company reputation is communicated between customers and stakeholders?

- What stories do people tell new employees about the company?

- What do people know about the history of the organisation?

- What do these stories say about the Culture of the business?

2. Rituals and Routines

This refers to the daily activities and actions of individuals within the organisation. Routines indicate what is expected of employees on a day-to-day basis, and what has been either directly or indirectly approved by those in managerial positions. However, very often, the more significant ones are consolidated by practice rather than by conscious decisions. Also, here, some questions are useful to frame the analysis of the element.

- What do employees expect when they arrive each day?

- What experience do customers expect from the organisation?

- What would be evident if it were removed from routines?

- What do these rituals and practices say about organisational beliefs?

3. Symbols

This includes all the elements that help give a visual representation of the company, both internally and externally. It contains logos, office space design, uniforms, slogans, colours, corporate image elements, some advertising, jingles and so on. Also, here, some questions are useful to frame the analysis of the aspect.

- What kind of image is associated with the company from the outside?

- How do employees and managers view the organisation?

- Are there any company-specific designs or jargon used?

- How does the organisation advertise itself?

4. Control Systems

These are the systems and tools by which the organisation is controlled. These can include both formal elements, such as the budgeting tool or the performance management system, as well as informal components, such as management style and communication routines.

- Which processes are strongly and weakly controlled?

- In general, is the company loosely or tightly controlled?

- Are employees rewarded or punished for errors?

- What reports and procedures are used to keep control of finance, etc.?

5. Organisation Structures

This refers to both the formal and informal organisation of the company. Alongside the formal Organisation Model, Johnson and Scholes also refer to the unwritten influence map, as well as what we would today consider the Internal Network.

- How hierarchical is the organisation?

- Are responsibility and influence distributed formally or informally?

- Where are the official lines of authority?

- Are there any unofficial lines of authority?

6. Power Structures

This is the genuine power structures and decision-making routines within the organisation. It may refer to a few executives, the CEO, board members, or an entire managerial level. These individuals are those who hold the most significant influence over decisions, and generally have the final say on meaningful actions or changes.

- Who holds power within the organisation?

- Who makes decisions on behalf of the company?

- What are the beliefs and Culture of those as the top of the business?

- How is the power used within the organisation?

The Cultural Web Model is widely used, sometimes with some variations or adaptations, as a Culture Audit tool, to check the elements that are more visible of the existing corporate Culture. It can also be used as a Change tool by working on intentionally designing the different components.

One of the positive elements of this model is its linking of formal and informal elements, giving to the Culture an indeed “web-like” structure that encompasses all decisions done within the organisation itself.

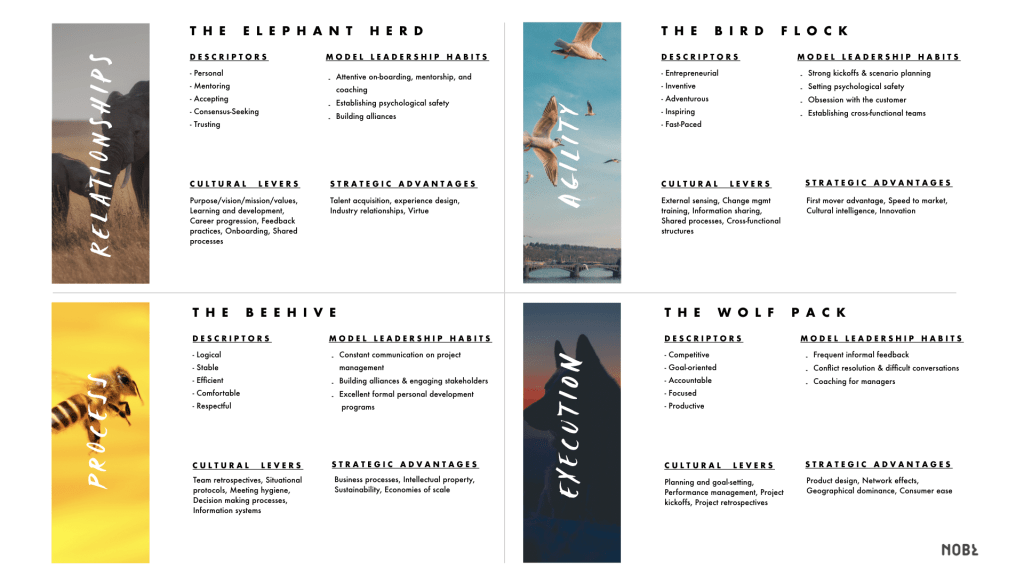

NOBL Culture/Market Fit Model

NOBL has developed a “Culture/Market Fit Model” that is loosely inspired by the Competing Values Framework. The idea is based on the concept that you can identify a potential market. But Then develop a culture that can deliver product/market fit. (NOBL Academy, 2019)

The model identifies four competing flavours of organisational Culture, each with unique traits and competitive strengths.

- The Elephant Herd: these cultures value interpersonal dynamics and relationships above all else. They are described by employees as being personal, mentoring, accepting, consensus-seeking, and trusting. These cultures tend to excel at strategies such as experience/service design, talent acquisition, and virtuousness. Think Patagonia, Pixar, and Zappos.

- The Bird Flock: these cultures value agility above all else. Employees use words like entrepreneurial, inventive, adventurous, inspiring, and fast-paced to describe these workplaces. Bird flocks tend to excel at cultural intelligence, customer intelligence, and of course, speed to market. Think Beats, Zara, and Netflix.

- The Beehive: these cultures value process and procedure above all else. Employees say these cultures feel logical, stable, efficient, comfortable, and respectful. Beehives often rock at achieving economies of scale, preserving intellectual property, and dominating on price. Think Toyota, GE, and Coca-Cola.

- The Wolf Pack: these cultures value execution and results above all else. Their employees use words like competitive, goal-oriented, accountable, focused, and productive to describe their workplaces. Wolf Packs can crush product design, geographical strategies, and capturing network effects. Think Facebook, Nike, and Bridgewater Associates. (NOBL Academy, 2019)

What is interesting is that NOBL suggests making the choice of Culture explicit through what they have defined a Culture Contract: It lays out the behaviours we expect to see if we’re truly upholding our values, why we believe they’re important strategically, and of course, what to do if we’re going off track (NOBL, 2020).

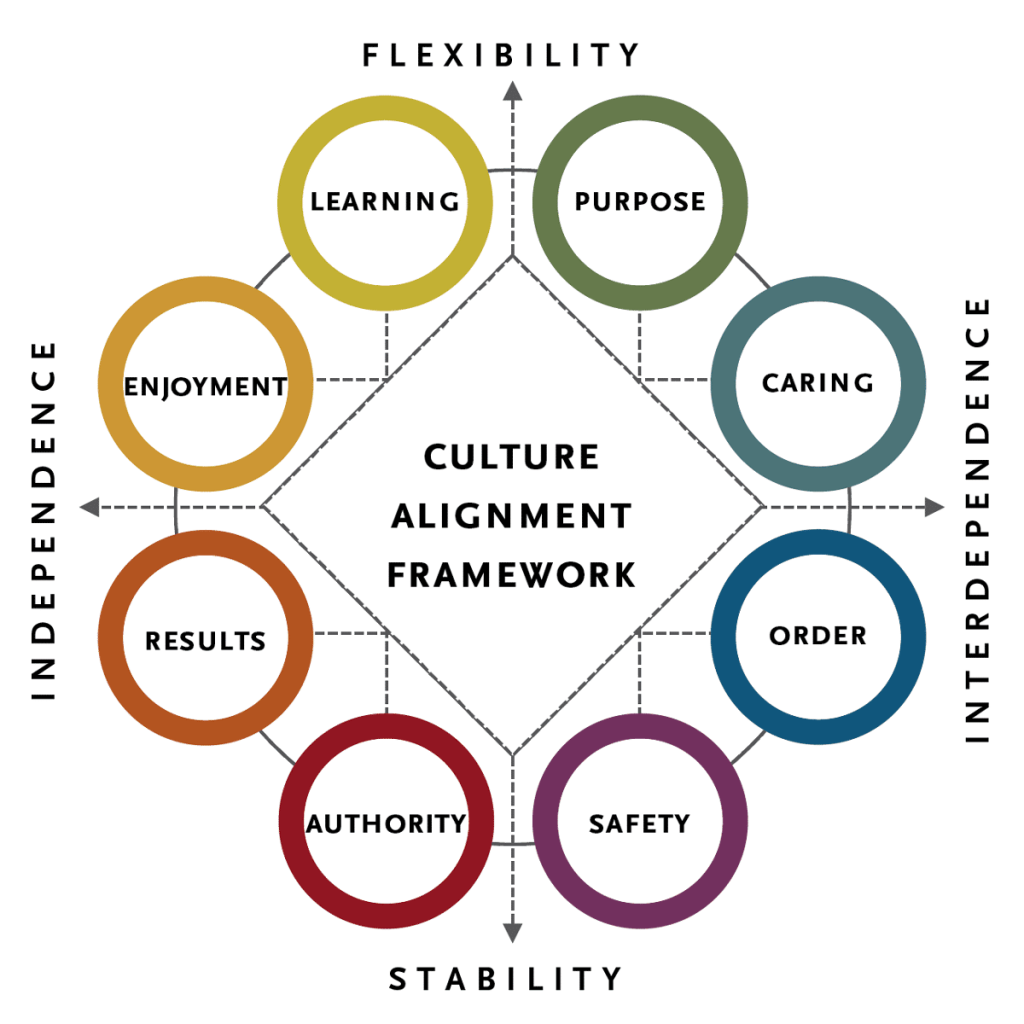

Organisational Culture Framework

Developed by Spencer Stuart, this framework looks at Culture by focusing on eight dimensions (Singh and Mark, 2017) presented in detail in a lengthy article on HBR (Groysberg et al., 2018).

The dimensions are identified on two axes: People Interactions and Response to Change through research of literature and a comparison of other models.

The eight styles identified are again balanced in the results of an organisation, as they are often blended in their existence. The model foresees that is easier to have the presence of two styles that are nearer in the model, versus two that are distant.

None of the styles is valid in absolute terms, they all have pros and cons, and they all can impact the overall effectiveness of the organisational Culture depending on the situation.

The approach further defines four levers that an organisation can use to develop their Culture:

- Articulate the Aspiration

- Select and develop leaders who align with the target culture.

- Use organisational conversations about Culture to underscore the importance of change.

- Reinforce the desired change through organisational design.

Organizational Culture Inventory (OCI)

The Organisational Culture Inventory is one of the most widely used organisational culture diagnostic tools (Cooke and Szumal, 1993).

Developed by Robert A. Cooke and J. Clayton Lafferty, the OCI provides an assessment of the operating Culture in terms of the behaviours that members believe are required to “fit in and meet expectations” within their organisation.

Four of the behavioural norms measured by the OCI are Constructive and facilitate problem-solving and decision making, teamwork, productivity, and long-term effectiveness. Eight of the behavioural norms are Defensive and detract from effective performance.

Results are plotted on the Human Synergistics Circumplex and reveal the shared behavioural expectations that operate within the organisation. It is possible to both do an AS-IS analysis but also include a TO-BE, ideal assessment.

Patterns of Cross Cultural Business Behavior

Richard Gesteland has championed the concept of Patterns of Cross-Cultural Business Behaviours published his ideas in 1999 with his book Cross-cultural Business Behavior (Gesteland, 2012). The context is that of marketing, but the approach that Gesteland uses to simplify cross-cultural behaviours has also been used in the context of integrations of multinational organisations, often after a merger or an acquisition.

The basic idea is that their patterns can contribute to bridging the cultural gap between countries, taking each other’s preferences into account and understanding where differences come from. As it is impossible to have information about the over 7000 local cultures existing, this model “simplifies” the world by providing four dimensions, investigated by the author.

1. Business, deal-focused cultures versus relationship-focused cultures

This dimension focuses on negotiation potential across cultures. Some are more focused on the business task, on one extreme, while others would be more focused on keeping human relationships on the other extreme. Risks of conflict are high when the two opposites interact because there is not an understanding of each individual focus.

2. Formal cultures versus informal cultures

This dimension focuses on communication and relationship, particularly with hierarchical positions in local Culture and status. In formal cultures, people prefer communication that respects status and functions, while in informal cultures, communication flows more freely. Als here, risks of conflict are high when there is no awareness of the style of the counterpart.

3. Rigid (monochrome) cultures versus fluid / accommodating cultures

This dimension focuses on the need for planning and precision, particularly in the usage of time, versus Culture where the relationship is more fluid. A typical cause of endless discussions is the respect of deadlines, which have different meanings for the two extremes. Respect of time is one of the most acute causes of controversies in multinational organisations and teams.

4. Expressive cultures versus conservative / reserved cultures

This dimension focuses on the communication style, but also the content. In one extreme, we have people that communicate loudly, with a lot of gestures and colourful expressions, often mixing personal as well as professional messages. On the opposite, the tendency to be quiet and calm while talking, and strictly to the “point” especially in terms of business content. This dimension often causes mistrust between people coming from the two sides, and this can lead as well to conflicting solutions.

This model is kind of a “quick fix” for many contexts that require an understanding of the impact of local cultures.

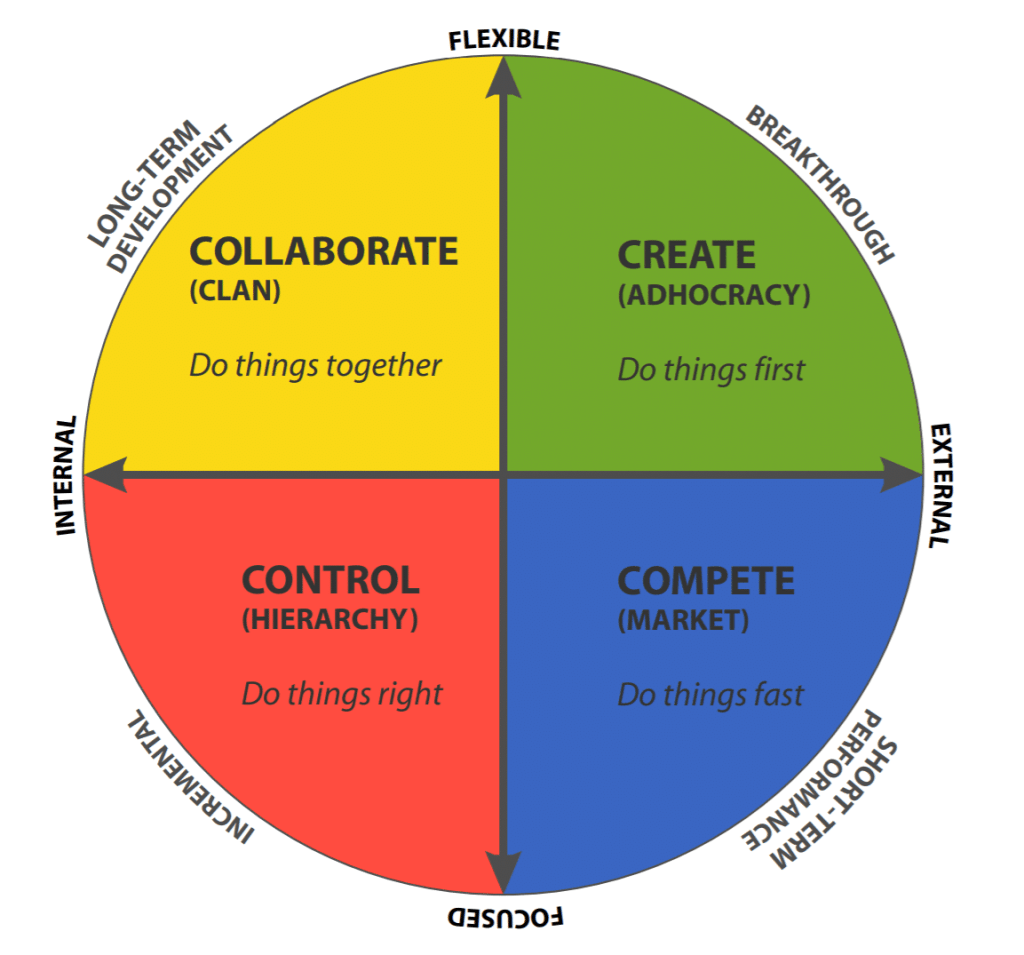

Schein’s Organisational Culture Model

Schein believed that Culture could be analysed at several levels that he articulated in successive developments of his research.

The first level of analysis is that of the visible Artefacts and Creations that encompass everything from the ways of dressing, office layout, behaviour patterns, to symbols stories and myths. These elements have the characteristic of being visible, but not always their impact can be fully understood.

The next level of analysis is the values that govern the behaviours of the members of the organisation. Here there is a level of awareness by the individuals, although often you may need to infer them from the individuals’ behaviours. But these only represent the visible manifestations or espoused values of Culture, i.e. they reflect the underlying Culture and act to justify actions and behaviour, but the reasons for behaviour remain hidden.

To understand an organisation’s Culture altogether, we need to move to a third level, that of the basic assumptions. These are the invisible and unconscious reasons for behaviour and are “taken for granted” by individuals. They are the unconsciously held learned responses which govern how organisational members think, act and behave.

Schein’s model explains why changes made solely at the level of Artefacts are likely to be short-lived and ineffective. It is therefore essential to act at the level of Values, having a conscious knowledge of the underlying Basic Assumptions that govern the organisation’s behaviours.

This model has had a thoroughly meaningful impact on the way organisations addressed Culture Change, which is visible by the push to define Value Statements capable of impacting the observable behaviours of organisations. Results have been mixed, and this is due to the variegated level of understanding of the Basic Assumptions.

An interesting aspect that descends from Schein’s model is the role of unlearning in a Culture Change process. For Schein, any program that includes a culture change needs to be transformative, thus requiring an unlearning of the old behaviours and new learning of the new ones. A principle that is valid in any change initiative that focuses on Culture.

Trompenaars Model of Organisation al Culture

Fons Trompenaars is famous for his research on National Cultures developed together with Hampden-Turner, whereby he identified seven dimensions of National Culture. The initial work was based on Hofstede’s model of National Cultures, but its definition was expanded to include different sizes and more specific focus on individual preferences (Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner, 2020).

- Universalism vs particularism, which looks at the importance of Rules vs Relationships.

- Individualism vs communitarianism, which looks at the importance of the individual vs the group

- Specific vs diffuse which looks at the involvement of people and the separation of private and professional lives.

- Neutral vs emotional which looks at how people express emotions.

- Achievement vs ascription, which looks at how people perceive status.

- Sequential time vs synchronous time which looks at how people manage time.

- Internal direction vs outer direction which looks at how people relate to their environment.

Similarly to Hofstede, also Trompenaars developed a framework to investigate corporate cultures, with a specific focus on Change (Woolliams and Trompenaars, 2003). He did so by identifying two dimensions of analysis and, like in some other of the models we have seen, identifying for stereotypes of organisational Culture.

The first dimension is egalitarian versus hierarchical – the degree of power distance between organisation members that are presumed to affect the degree of (de) centralisation in an organisation. Hence, we have egalitarian/decentralised: people are equal, and decision making power is decentralised. And hierarchical/centralised: people differ in position power, and decision-making power is centralised, so the leaders decide and tell the employees what to do.

The second dimension is the people versus task orientation, combined with an (in)formal style – presuming that a task orientation aligns with a more formal communication style. The model creates four quadrants

| Incubator Culture (egalitarian and person-oriented) | Family Culture (hierarchical and person-oriented) |

|

|

| Eiffel Tower Culture (hierarchical and task-oriented) | Guided Missile Culture (egalitarian and task-oriented) |

|

|

It’s easy to see similarities between this model and the Competing Values Framework, although there is not a perfect match. I’ve used this model extensively in the past and is powerful when you consider that all these models can coexist in an organisation, and you try to operate on a fill-gap basis.

Summing Up

As with other components of Organisation Design, there’s a vast number of options to choose from in terms of models and approaches. I don’t see this as confusion, but rather as a testimony of the importance of the topic and the need to focus on the topic itself. In the case of Culture, it is interesting to notice how relevant the linkage between this component and the organisational model is in most of the frameworks presented. The logic that you cannot truly change Culture without also considering the organisational consequences is a further element that supports my concept of Intentional Design.

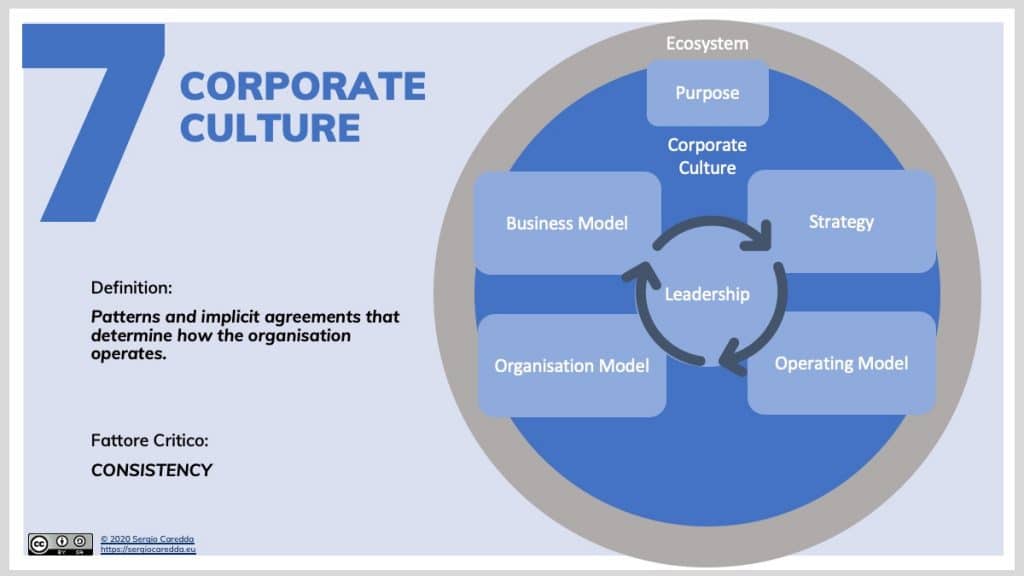

Culture within the Organisation Evolution Framework

I’ve recently introduced a Visual Framework that allows visualising all essential building blocks of Organisation Design. Culture is the seventh building block of the model and is the seabed of consistency for all other organisation design elements.

My working definition for Corporate Culture is the patterns and implicit agreements that determine how the organisation operates.

It’s evident from this long article that this definition gives only a partial glimpse in the world of culture. I also decisively don’t take a stance in the debate between considering Culture an independent or dependent variable. The reason is simple: I see merit in both approaches, and both propose tools and instruments that, if applied intelligently, can serve to support both the understanding of an existing culture, and the crafting of a new one.

Again, feel free to give feedback, and suggest any model that I might be missing in this article, using the comment section below. Thank you!

Reference list

Bate, S.P. (1995). Strategies for cultural change. Routledge.

Cameron, K. (2011). An Introduction to the Competing Values Framework. [online] Haworth. Available at: https://www.thercfgroup.com/files/resources/an_introduction_to_the_competing_values_framework.pdf.

Cameron, K.S. and Quinn, R. (2005). Diagnosing and Changing Organizational Culture: Based on the Competing Values Framework. John Wiley & Sons.

Cancialosi, C. (2017). What is Organizational Culture? | Complete Definition and Characteristics. [online] gothamCulture. Available at: https://gothamculture.com/what-is-organizational-culture-definition/ [Accessed 25 Nov. 2020].

Cooke, R.A. and Rousseau, D.M. (1988). Behavioral Norms and Expectations. Group & Organization Studies, 13(3), pp.245–273.

Cooke, R.A. and Szumal, J.L. (1993). Measuring Normative Beliefs and Shared Behavioral Expectations in Organizations: The Reliability and Validity of the Organizational Culture Inventory. Psychological Reports, 72(3_suppl), pp.1299–1330.

Cummings, T.G. and Worley, C.G. (2016). Organization development and change. 10th ed. Toronto: Nelson Education.

Davis, S.M. (1984). Managing corporate culture. Cambridge (Mass.): Ballinger Publishing.

Deal, T. and Kennedy, A.A. (1982). Corporate Cultures the Rites and Rituals of Corporate Life. 1st ed. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

Denison, D.R. (2012). Leading culture change in global organizations : aligning culture and strategy. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Gesteland, R.R. (2012). Cross-cultural Business Behavior : a Guide for Global Management. 5th ed. Copenhagen: Copenhagen Business School Press.

Goldminz, I. (2020). The competing values framework & Culture Contract [Quinn & NOBL]. [online] Medium. Available at: https://medium.com/org-hacking/the-competing-values-framework-culture-contract-quinn-nobl-7d1471c2cbe9.

Groysberg, B., Lee, J., Price, J. and Cheng, J.Y.-J. (2018). The Leader’s Guide to Corporate Culture. [online] Harvard Business Review. Available at: https://hbr.org/2018/01/the-leaders-guide-to-corporate-culture [Accessed 25 Nov. 2020].

Hall, E.T. (1976). Beyond culture. New York, Ny: Anchor Books.

Handy, C.B. (1993). Understanding organizations. New York: Oxford University Press.

Handy, C.B. (1996). Gods of Management: the Changing Work of Organizations. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hofstede, G. (1985). Culture’s Consequences : Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and Organizations across Nations. 1st Edition ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage.

Hofstede, G. and Hofstede, J.G. (2005). Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. New York: Mcgraw-Hill.

Kotter, J.P. and Heskett, J.L. (1992). Corporate culture and performance. Toronto, New York: Free Press.

Lundy, O. and Cowling, A. (1996). Strategic human resource management. London ; New York: Routledge.

Maull, R., Brown, P. and Cliffe, R. (2001). Organisational culture and quality improvement. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 21(3), pp.302–326.

Mulder, P. (2017). What are Patterns of Cross Cultural Business Behavior? [online] toolshero. Available at: https://www.toolshero.com/marketing/patterns-cross-cultural-business-behavior/ [Accessed 25 Nov. 2020].

Needle, D. (2004). Business in context : an introduction to business and its environment. London: Thomson.

NOBL (2020). Culture Contract. [online] The Blast Newsletter. Available at: https://mailchi.mp/nobl/culture-contract [Accessed 25 Nov. 2020].

NOBL Academy (2019). The Only Thing More Important Than Product/Market Fit. [online] NOBL Academy. Available at: https://academy.nobl.io/the-only-thing-more-important-than-product-market-fit/ [Accessed 25 Nov. 2020].

OpenLearn (2019). Management: perspective and practice. [online] OpenLearn. Available at: https://www.open.edu/openlearn/money-business/leadership-management/management-perspective-and-practice/content-section-3.5.1 [Accessed 25 Nov. 2020].

O’Reilly, C. and Chatman, J.A. (1996). (PDF) Culture and social control: Corporations, cult and commitment. Research in Organizational Behavior, [online] 18, pp.157–200. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/308175661_Culture_and_social_control_Corporations_cult_and_commitment [Accessed 25 Nov. 2020].

Ouchi, W.G. (1981). Theory Z: How American Business Can Meet the Japanese Challenge. Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley.

Quinn, R.E. and Rohrbaugh, J. (1983). A Spatial Model of Effectiveness Criteria: Towards a Competing Values Approach to Organizational Analysis. Management Science, 29(3), pp.363–377.

Ravasi, D. and Schultz, M. (2006). Responding to Organizational Identity Threats: Exploring the Role of Organizational Culture. The Academy of Management Journal, [online] 49(3), pp.433–458. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20159775 [Accessed 25 Nov. 2020].

Schein, E.H. (1984). Coming to a New Awareness of Organizational Culture. [online] MIT Sloan Management Review. Available at: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/coming-to-a-new-awareness-of-organizational-culture/.

Schein, E.H. and Schein, P. (2017). Organizational culture and leadership. 5th ed. Hoboken: New Jersey Wiley.

Schrodt, P. (2002). The relationship between organizational identification and organizational culture: Employee perceptions of culture and identification in a retail sales organization. Communication Studies, 53(2), pp.189–202.

Schwartz, T.P., Deal, T.E. and Kennedy, A.A. (1983). Corporate Cultures: The Rites and Rituals of Corporate Life. Contemporary Sociology, 12(5), p.566.

Singh, S. and Mark, S. (2017). Thinking about Culture. [online] http://www.spencerstuart.com. Available at: https://www.spencerstuart.com/research-and-insight/thinking-about-culture-five-questions.

Smircich, L. (1983). Concepts of Culture and Organizational Analysis. Administrative Science Quarterly, 28(3), p.339.

Sull, D., Sull, C. and Chamberlain, A. (2019). Measuring Culture in Leading Companies. [online] MIT Sloan Management Review. Available at: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/projects/measuring-culture-in-leading-companies/?og=culture500 [Accessed 25 Nov. 2020].

Sun, S. (2009). Organizational Culture and Its Themes. International Journal of Business and Management, 3(12).

Trompenaars, F. and Hampden-Turner, C. (2020). Riding The Waves Of Culture. 4th ed. S.L.: Mcgraw-Hill Education.

Williams, A.P.O., Dobson, P. and Walters, M. (1996). Changing Culture : New Organizational Approaches. London: Institute of Personnel and Development.

Woolliams, P. and Trompenaars, F. (2003). A New Framework for Managing Change across Cultures. Journal of Change Management, [online] 3(4), pp.361–375. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265612411_Managing_Change_Across_Corporate_Cultures [Accessed 25 Nov. 2020].

Yu, T. and Wu, N. (2009). A Review of Study on the Competing Values Framework. International Journal of Business and Management, [online] 4(7). Available at: http://ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/ijbm/article/view/3000.

Cover Photo by Mimi Thian on Unsplash

[…] Corporate Culture: The Theory and the Practice […]

[…] Corporate Culture: The Theory and the Practice […]

[…] Creda, S. (2020, November 6). Corporate Culture, The Theory and The Practice. https://sergiocaredda.eu/organisation/organisation-design/corporate-culture-the-theory-and-the-pract… […]

Kudos! This is the most comprehensive list of frameworks I have come cross. Really helped build perspective. Keep it up!

[…] Caredda, S, 2020. Corporate Culture: The Theory and The Practice. [online] Available at: https://sergiocaredda.eu/organisation/organisation-design/corporate-culture-the-theory-and-the-pract… […]

[…] Caredda, S. (2020). Corporate Culture: The Theory and the Practice | Sergio Caredda. https://sergiocaredda.eu/organisation/organisation-design/corporate-culture-the-theory-and-the-pract…. […]

[…] Corporate Culture: The Theory and the Practice […]

[…] Corporate Culture: The Theory and the Practice […]