- What is Organisation Design?

- Introducing the Organisation Evolution Framework

- Consistency and Intentional Design. Building the Organisation of the Future.

- Building the Intentional Organisation

- Business Models: the theory and practice

- Strategy Frameworks: The Theory and the Practice

- Organisation Models: a Reasoned List between Old and New

- Operating Models: the theory and the practice.

- Leadership Models: The Theory and the Practice

- Purpose: The Theory and the Practice

- Corporate Culture: The Theory and the Practice

- Organisation Ecosystem: The Theory and the Practice

Ecosystem is the eighth building block of the Organisation Evolution Framework, and is the last element we will explore. This article will be different than the other in this series, because I will not explore different approaches or definitions towards ecosystems, but rather look at how we can identify the elements within an ecosystem. I will also dedicate a lot of time in trying to clarify the definition of what an Ecosystem is, and how we can best use the biological metaphor to add to the understanding of this very relevant organisation dimension.

Defining the Ecosystem

Finding an adequate definition of Ecosystem is not easy. Partly the reason is that we use a biological metaphor, without assessing if all the features of a biological ecosystem can also be traced into an organisational one. The reality, as we see, is that a large area of organisational study has narrowed down the concept of ecosystems in a business concept more akin to a specif form of alignment between organisations, rather than considering really all features of a biological ecosystem. Particularly, there is a tendency for management audiences to consider the ecosystem metaphor with a positive allure linked to the misguided belief that nature designs systems such that they exhibit long-term stability across interconnected structures. The reality is that this is an exception, and biological ecosystems are not designed, but rather emerging phenomena. (Mars and Bronstein, 2017).

In any case, the concept of business ecosystem has widely developed in recent years, particularly after the publication of Moore’s book The death of competition in 1996.

Fig.1: Ngram of usage of the term “business ecosystem” between 1960 and 2019 from Google Books.

Environment vs. Ecosystem

But first thing first. I chose to use the word Ecosystem and not Environment for a number of reasons that will become clearer through this article. I wanted however to start by borrowing the simplest definitions that are used in biology. The Environment is what surrounds and organism, including both biological organisms and non-living components. An Ecosystem is, instead, the community of organisms along with non-living components where the biotic and abiotic components are in continuous interaction with each other.

This element of interaction is key, and the one I am more interested to explore, as through these interactions the organisation will be able to create value. The way I see it, is that any stakeholder interacting with a specific organisation, constitute part of an ecosystem. This puts things already in perspective, as an organisation cannot simply apply an extractive mindset, but needs to develop a community-like interaction mechanism.

As with all the other elements of the Organisation Evolution Framework, we will see that also Ecosystem is affected by the polarity emergence/intentionality. We will see later on who this impact the concept of intentional design. At this stage it is important to make sure you understand that I am referring to Ecosystem is the broadest possible sense, much nearer to the original biological metaphor, than most business literature often does.

Organised Ecosystems

When talking of Ecosystem I am not referring to specific business constellation (as for example can be found in Jacobides, Cennamo and Gawer (2018). The way I am forming my definition (as usual this is a work in progress, so happy to discuss this further) is that I see an ecosystem not as a specifically organised interaction pattern between composing actors, but rather as a subset of the environment in which an organisation act, based on a number of relationships the organisation builds.

Over the past 20 years, the term “ecosystem” has become pervasive in discussions of strategy (Adner, 2016). This originated from the work of James F. Moore, who captured the attention of management over a new pillar (Moore, 2006) of business thinking, on the side of Hierarchy and Markets (usually identified as the core elements of design as per Coase, 1937). As it developed, the notion of ecosystems has raised awareness and focused attention on new models of value creation and value capture (Adner, 2016), but this way to narrowed down to identifying ecosystems as a specific way of collaboration or alignment or as intentional communities of economic actors (Moore, 2006).

My view is that, essentially, every organisation is always part of an ecosystem from the moment it starts existing and intentionally creates the first connection. Customers would be the most typical example of this first type of interactions, but so would also be candidates through the recruiting process, suppliers, shareholders the moment the organisation get listed, or other funding partners. Every organisation exists within a web of relationship that create value. Thus, organizational ecosystems should be mostly understood as emergent phenomena that result from a tenuous balance between actor agency and social structure, rather than from purposeful engineering. (Mars and Bronstein, 2017)

This would be much more in line with the real power of the ecosystem metaphor.

The Ecosystem as a Biological Metaphor

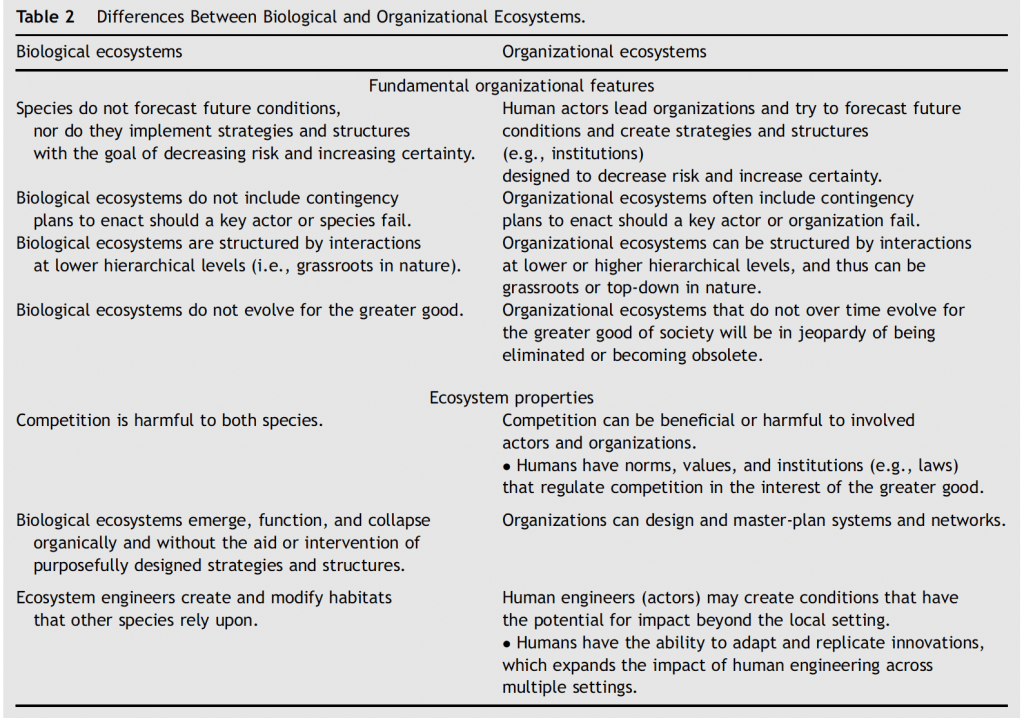

The work of Mars, Bronstein and Lush (2012) provides an accurate picture of the similarities and differences between the usage of ecosystem as an organisational metaphor and the true ecosystem in biology. I have used the tables they produced to consolidate the findings in terms of similarities (Figure 2) and Differences (Figure 3).

The most important similarity is that they are emergent phenomena, i.e. there is not a plan or done design. There are different types of actors, with different types of specialisation. Plus, the resiliency of a given organisational ecosystem is likely to be positively influenced by the degree of diversity of the actors and organisations within. What is most important, as the authors observe, is that existence per se is not a

trustworthy measure of the general health, functionality, or persistence of either biological or organizational ecosystems.

This last element is critical to understand why the narrow view of organised ecosystems we have seen above can be misleading. That idea assumes a certain level of organised planning, a direction, and ends up assuming that if the the ecosystem exists, this is positively creating value. In biology, the reality is that an ecosystem may degrade at a rate below the level of detection. Moreover, it may appear to be robust until a set of specific conditions is modified.

As with all metaphors, we need to accept that there are also differences. The authors have identified a few:

The biggest trait is that ecosystems in the realm of organisations are somehow the produce of human action. As such, they tend to display the impacts of intelligence and activity of humans. In biological ecosystems, for example, competition is always harmful, whereas in organisational ecosystems it can be beneficial depending con circumstances.

Most notably, however, biological ecosystems miss any form of planning, whereas organisational ecosystems have at least a minimum level of planning features, linked to the action of individuals within organisations that compose the ecosystem itself.

The above makes me think that the direction I chose to consider Ecosystem as the “playing field” for organisational interaction is correct, but we need to make sure we play by the rule of the metaphor, also understanding “collectively” the different elements that compose and impact the ecosystem. Reasoning in “ecological terms” I believe it is important to understand a few corollary definitions.

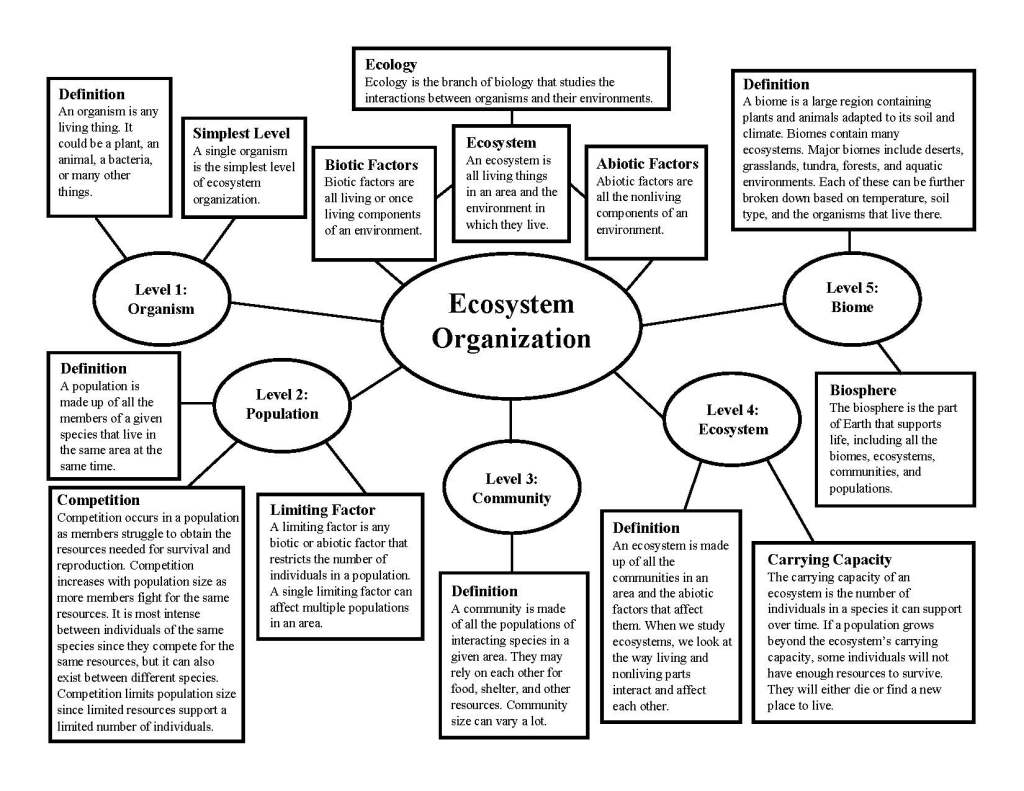

Ecosystem Organisation

I found online this great representation of the key components of Ecosystem Organisation from an ecology point of view.

The first consequence of correctly aligning with the biological metaphor, is that we should consider that an Ecosystem is composed both of Biotic and Abiotic factors. Translated into our organisational setting, I’d be considering abiotic factors all the “non-living” resources from an organisational point of view. This can be financial resources, natural resources, laws and norms, technology systems that can be accessed by the organisation and so on. To a certain extend the definition of “non living” resource here can be difficult to define, what is important is to consider also these elements as part of the picture.

Then there are five composing levels to be considered:

- Organism. This is akin to the individual organisation, but the beautiful aspect of continuing with the metaphor is that also an organisation can be an ecosystem at its simplest level.

- Population. This is a concept that is not often used, but equates to aligning types of organisation together. Reality is that we do use concepts of populations also in org design, for example when we classify some as customers. Interesting here the concepts of competition (with the caveat we have seen above) and Limiting Factor, which essentially has to do with resources.

- Community is an intermediate level still below the ecosystem, whereby the clear distinctive element is interactions among the populations.

- Ecosystem is the level we are more interested into, whereby the most interesting aspect to be looked at is carrying capacity. Which, translated, is what I refer to sustainability: i.e. is the number of organisms it can support.

- Biome is the largest level of ecosystem, or, we could say, a collection of ecosystem. In an organisation design world, we can see this as an entire industry, or maybe the entire market.

Does this all add up also into your head now? Before moving forward, there is still one concept I want to focus on from biology, and that is particularly relevant in ecosystems.

Co-evolution

Co-evolution is a core concept in studies of complex adaptive systems and the economy, focusing attention on reciprocal cycles of adaptation among one or more elements of an economic system. The idea stems, once more, from biology and evolutionary theory, and looks at evolution of two or more species which reciprocally affect each other, sometimes creating a mutualistic relationship between the species. Darwin himself mentioned the concept when describing the interaction between some flowers and pollinating insects (although he did not use the word).

Applied to organisations, this concept has been the core in the development of the approach to ecosystems by Moore (1996) and subsequent studies (Iansiti and Levien, 2004) focused on demonstrating the impact of reciprocal interactions among technologies, business processes, products and services, market mechanisms, firm and policy and regulation.

Co-evolution is, from my point of view, a distinctive trait of an ecosystem. As we continue in the biological metaphor, we can clearly see why there is not a need to direct evolution, plan it or architect it. It can simply happen, as an emergent feature of the system.

Interdependence

A second trait that is often looked up into ecosystems is interdependence, also seen as an attribute of complex adaptive systems. There can be multiple ways of analysing interdependence between the different parts of a system, but the most important one is that all organisms in an ecosystem depend upon each other. If the population of one organism rises or falls, then this can affect the rest of the ecosystem.

This characteristic is the most important to watch when we reason in terms of ecosystem. Why? Because most of the business literature has been skewed to only look at competition as a qualifying factor for company’s survival. But that is only one of the forms of interactions (and, as mentioned before, we should also not kill the possibility of competing). After all, the entire literature around ecosystems started when managers and observers alike, started seeing that there where positive value flows in cooperating mechanisms also within a capitalistic market framerwork.

Moving towards a plausible definition

With all the above said, let’s move now to my working definition of Ecosystem. We will then examine how an ecosystem can be mapped, and what we should consider in terms of balancing act between emergence and intentionality.

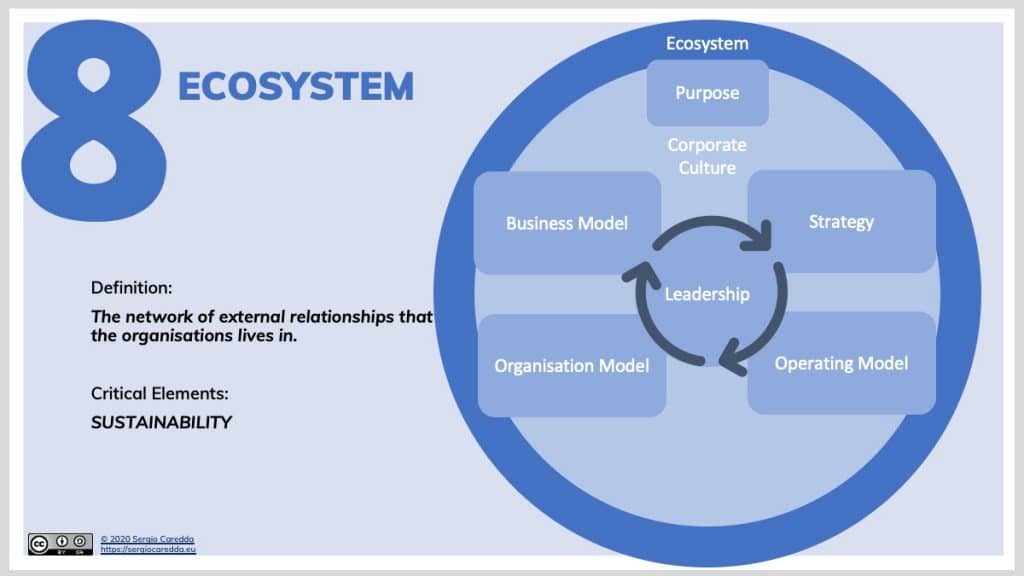

Ecosystem in the Organisation Evolution Framework.

I’ve recently introduced a Visual Framework that allows visualising all essential building blocks of Organisation Design. Ecosystem is the eighth building block of the model and is the outside world in which an organisation exists.

My working definition of it is:

The Network of external relationships that the organisation lives in.

The critical element it supports is sustainability. Why? Because there should always be a long-term view in analysing the value of relationships within the ecosystem. As we have seen above, ecosystems are characterised, in biology, by a “carrying capacity” and by a concept of interdependence. If we trust these two elements to be true, the consequense is that our organisation needs to pursue long term sustainability of its interactions with the environment.

Analysing the Components of an Ecosystem

Now that we have defined what an ecosystem is, we need to understand what are its components, which one are relevant and how we should include them into our organisation design perspectives. In this section, I will talk about a methodology that can be very useful for identifying the key “organisms” present in an ecosystem: stakeholders mapping. I will then try to cover how relationships and connections work based on the concept of value.

Looking at Stakeholders

A good way to understand an ecosystem is Stakeholders Mapping. This discipline belongs normally to Change Management, and has been used often to identify the key actors impacted by a specific change process. We find examples of Stakeholders Mapping also at an individual level (for example thinking in terms of career), as well as more systematic approaches often linked to Corporate and Social Responsibility or Public Institutions (World Bank, 2005).

In general we can identify stakeholders as the individuals, groups, or other organizations that are affected by and also affect the firm’s decisions and actions (Freeman, 1984). This definition aligns well with the concept of “ecosystem” we have seen above, and the interdependence mechanism we have seen. This is why i find it useful to associate this methodology to the topic.

The 21st Century is one of “Managing for Stakeholders.” The task of executives is to create as much value as possible for stakeholders without resorting to tradeoffs. Great companies endure because they manage to get stakeholder interests aligned in the same direction.

R. Edward Freeman

From a firm’s perspective, the concept of stakeholders has originated through three different perspectives.

- The Separation Perspective is based on an agency’s view of managers, working in the interest of shareholders, very much in line with Friedman’s work. According to this perspective managers should take decisions benefiting other stakeholders only when this would also benefit shareholders.

- The Ethical Perspective looks at a way by which organisations have an obligation to conduct themselves in a way that treats each stakeholder group fairly. This view does not disregard the preferences and claims of shareholders, but takes shareholder interests in consideration only to the extent that their interests coincide with the greater good. This perspective is very much aligned to political science considerations, and the role that the Human Rights declaration, for example, played in recent years.

- The Integrated Perspective derives directly from Systems’ Thinking approaches, and states that firms cannot function independently of the stakeholder environment in which they operate, making the effects of managerial decisions and actions on non-owner stakeholders part of decisions and actions made in the interests of owners (Droege, 2008). This is the perspective that is being reinforced also after some of the largest scandals in the financial world, and looks at the complex “duties” that organisations have towards the public.

It’s easy to see where I’m going in terms of perspective, as the concept of Ecosystem with its interdependence assets looks at stakeholders in an integrated way. It is the concept itself of the Organisation Evolution Framework to offer managers a view of the “ecosystem” that needs to consider all relevant actors part of the decision making process, and not just parts of them.

There are also other views of Stakeholders which depend on different ontological oppositions, brilliantly summarised in figure 6 (Walker, Bourne and Shelley, 2008).

The above lists a number of perspective which add value to why mapping stakeholder is useful, not just from a political point of view, but rather because of the complexity of view they carry.

Typically Stakeholders are organised into groups (akin to the population concept we have seen above). Let’s see the most important one:

- Customers: i.e. all the stakeholders that interact with the organisation requesting products or services.

- Suppliers: i.e. all those providing the organisation with products or services.

- External Workers: employees are normally considered part of the organisation, but most organisation today use the work of a number of different actors with different contractual arrangements. We should consider these as well, also including other people gravitating around the organisation: Candidates and Alumni.

- Government: i.e. all those institutions providing rules, norms and having the right to enforce and inspect the organisation.

- NGOs: i.e. all those organisations not affiliated to a government that provide framework of references or pressure around specific issues that can influence the firm.

- Shareholders: these are effectively the entities that have formal stakes in the organisation, from a contractual point of view.

- Financial Institutions: these are the organisations that provide financial resources for the organisation to exist. I am setting them up separately as, in some situations (think about start-ups), their involvement is key.

- Vertical Chains: these are the entities that are linked as customers of our customer and suppliers of our supplier. With the vertical integration processes that many indiustries have seen, we need to consider these as well.

- End consumer in many industries the end consumer is a distant connection, yet we need to consider these specifically also because of the specific protection that many government have guaranteed to them.

The list is probably incomplete, and depending on the industry we might want to specify some categories or subcategories. In my experience the above helps framing the key players in our ecosystem.

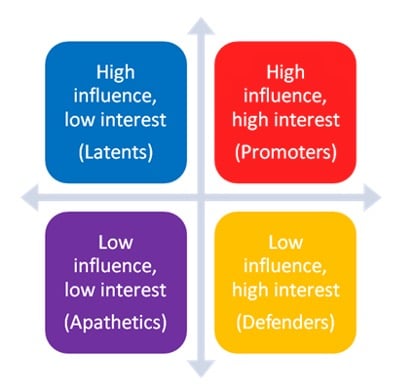

Stakeholders Analysis

However, we are not interested to just produce a long list of actors. We need to understand their relationship with the organisation.

A typical tool used to map stakeholder uses a four quadrant matrix organised around the lines of interest and influence. As such Stakeholder analysis (stakeholder mapping) is a way of determining who among stakeholders can have the most positive or negative influence on an effort, who is likely to be most affected by the effort, and how you should work with stakeholders with different levels of interest and influence (Rabinowitz, 2018).

The idea of this basic classification is to prioritise relationship with specific stakeholders, adapting communication, involvement and in general connecting activities.

It is definitely useful when managing change processes and programs, as well as addressing strategic moves where an outside in perspective is needed. However, we need to be careful in the mapping of the stakeholders, not to limit us just towards their influence and interest for the organisation.

First of all, we need to accept that these dimensions are changing all the time, and as such, a rigid classification can be problematic.

Secondly, how do we measure Interest and Influence consistently? We need to discuss this further, and I think that an important element to consider is how relationship happens.

Identifying relationships through Value

We have already seen, when discussing Business Models, the role that Value Proposition has in terms of building an organisation set-up. Thinking in terms of ecosystem adds the perspective of the recipient of that Value, making value creation an objective not just for the organisation, but also for the entire ecosystem.

We have already seen that current measures of value are limited in capturing what value really is. Yet it is interesting to notice that all the measures that exists are linked to relationships built within an ecosystem. We are used to think that a P&L of a firm tells the truth about its value… but reality is that accounting is based on generally accepted principles, a discipline that evolves around a number of actors that co-developed a methodology that offers a good proxy of value measurement. Not dissimilarly we are seeing today many effort in evaluating impacts, for example in Sustainability Reporting.

What is important is to make sure we understand Value from the perspective of the stakeholder. This oustide-in perspective is critical in defining and understanding how different actors of the ecosystem act. Perceived Value is the critical factor in assessing the quality and intensity of the relationships established with the other actors.

Let’s think about a real-life example. We can state that a company like Apple is today present in multiple ecosystems. When it launched the iPod, it created a new “market” for music, and after that, with the launch of the iPhone, it created a new market for app developers and so on. This have been often labelled as ecosystems in the narrower sense of what we have seen before, but let’s explore the issue a bit further. The iPhone has developed, over the year, often more as a picture and film-taking device rather than as a communication one. Services like Instagram or Tik-Tok entirely rely on this aspect, even if, apparently, there is no commercial relationship between the companies. The same can be said about the plethora of start-ups that produce calendars, posters, print-outs of photos done with these cameras. Some would immediately point to network effects caused or facilitated by technology. But we tend to forget that most of these relationship are, at start, not of economic value, but are value-adding.

The value of an ecosystem is today much higher than the sum of its components, exactly because of the large number of non-economic interactions that happen within it. So how does an individual organisation shape these value chains? Essentially through Purpose, which defines the way the organisation interacts with the external environment, setting the scene of what it values, and through the Business Model, which defines the value proposition the organisation wants to offer. With these two components it defines the way it want to interact with the other organisms in the ecosystem, what it wants to offer, and how it wants to interact.

Markets as Value Proxy

Markets are, in my mind, a specific form of ecosystems, whereby trade is the most prominent form of echange of value. In history, markets have shown to be fairly effective in assessing the value of something, despite multiple distortions they carry. As such markets are a good proxy to define value of transactions, but should not considered an absolute truth.

This essentially for two reasons. First and foremost, also in market ecosystems there are non-market transactions present. And we need to make sure that we cater for those as well. Secondly, as seen above, competition is not the only driving force of organisational ecosystems. We need to ensure that also certain level of cooperation exists, and these are rarely dominant in a market-like scenario.

Despite these two caveats, we are seeing more and more often examples of organisational settings that are exploiting the advantages of thinking in terms of ecosystem and using market logic as guidance for valuation. This is the example of the rendanheyi model of Haier, whereby the concept of ecosystem based ion market logic is applied within the organisation. This causes an important consequence in today’s organisational scenario: boundaries between what is internal and external to an organisation are fading, and even looking at the most stable form (usually based on legal contracts), do not allow to have certainty.

There are many ways where an ecosystem logic can be a valuable tool to enhance an ecosystem. We see this being applied in many aspects within organisations, from internal talent marketplaces, to internal crowdsourcing applied to innovation ideas and so on. The idea is to look at how competition as well as market-defined funding mechanism can support the development of an ecosystem.

Why do these forms work well? Because market logic is very efficient to visualise and distribute incentives from a human point of view. Getting your personal idea sold, challenging other ideas, prevailing on the market, are all elements that seem to link well with the way our psychology works. What is important, is to make this happen within a context that is regulated within a framework of reference that makes sense. We need to avoid, however, the logic of competition as predators and prey, looking to consistently review the concept of interdependece we have seen above.

Multiple Ecosystems

There is one last question to be answered. As an organisation, do you belong to one and only ecosystem, or is it possible to belong to more ecosystems? I’ve already dropped a sentence in this article that suggests that my view is that you canm belong to multiple ecosystems. This especially applies to large scale organisations that address different markets or are present in different industries, or simply because you act in different territories.

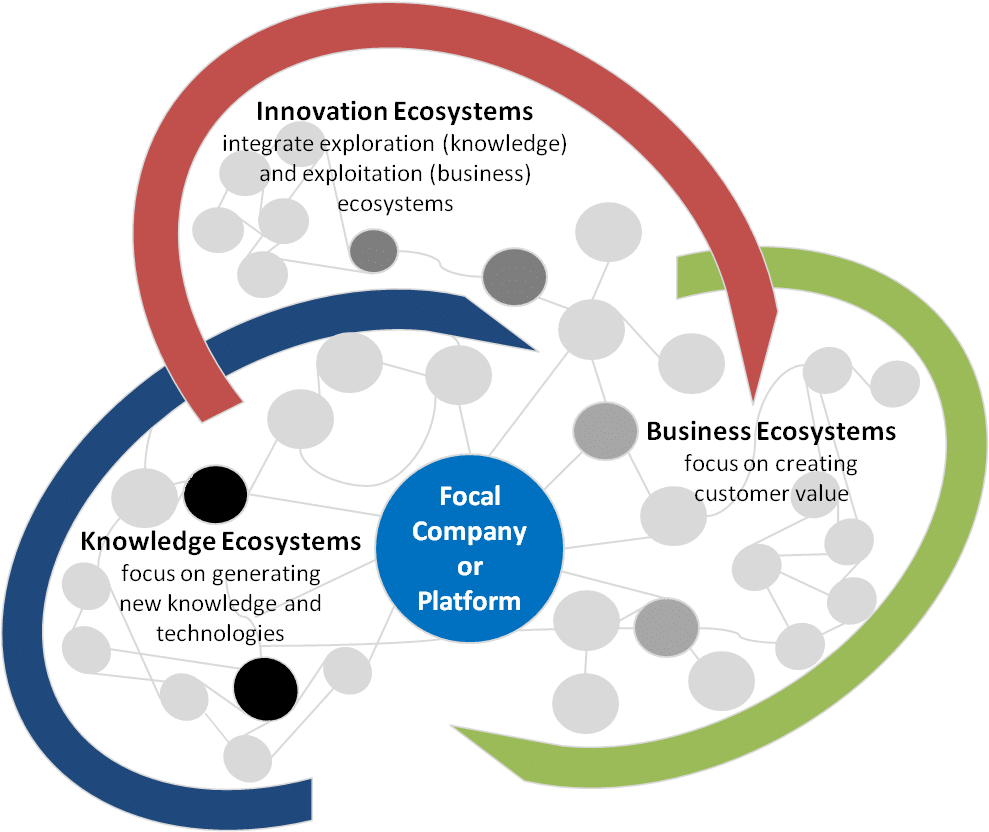

When talking about ecosystems, several authors have focused on concepts related to business (thus focused on value creation), while others linked the term to innovation creation, and other to the concept of knowledge sharing.

All these three characteristics are relevant as we discuss ecosystems, and it is very well plausible that each organisation is part not of one, but of at least three different ecosystems, based on the nature of the exchanges that happens.

Figure 8 represents this synthesis: Business ecosystems focus on present customer value creation, and the large companies are typical key players within them. Knowledge ecosystems focus on the generation of new knowledge, and in this way research institutes and innovators, such as technology entrepreneurs, play a central role in these ecosystems. Innovation ecosystems occur as an integrating mechanism between the exploration of new knowledge and its exploitation for value co-creation in business ecosystems (Valkokari, 2015).

What is important to notice is that all ecosystems are dynamic and never static, and also the definition of multiple belonging is not easy to always differentiate, also because the concept of value as determinant only for one of the ecosystem, is for me limiting. However, it is important to notice that this explanation is still valuable, in order to understand that we need to consider more than one approach as we check the nature of the relationship with the outside world.

Intentionality in an Ecosystem

As we have seen above, one of the key differences between an ecosystem in biology, and the application of its metaphor to an organisation context is that human organisations can be planned. Thus, an ecosystem can be designed, and this is an additional reason why I have included the term ecosystem and not environment in the Organisation Evolution Framework.

The idea that entire ecosystem can be designed is, however, misleading. Even when we think at ecosystems organisations, the fact that one focal actor starts building the ecosystem around a strategic intent, does not mean that the final result will be totally according to plan. I doubt, for example, that what the Apple Store is today was really carefully planned by Steve Jobs upon the launch of the iPhone.

What is important to notice, however, is that every organisation has the duty of applying a certain degree of intentionality in designing its relationship with the environment. There are already a few elements around this that we have seen, but that now come up into a renewed context:

- Purpose: is essential to define the concept of value the organisation wants to propose to the outside world, also possibly in terms of moral contribution, basically answering the question why do we exist.

- Business Model: is the foundation of the value proposition of what the organisation wants to exchange with the market, for example in terms of services or products, basically specifying what we are offering.

- Strategy: defines the priorities on how we interact with the external environment, essentially shaping what we will consider our ecosystem. It does so by figuring out what are our main partners and stakeholders.

- Operating Model: will define the how we interact with the ecosystem especially in terms of multi-belonging to the innovation and knowledge development aspects.It does so by figuring out how value is created internally and externally, also identifying critical relationships.

- Organisation Model: is foundational by choosing how work is done and what the boundaries of the ecosystem will be in terms of who’s in or out depending on the working relationships.

- Leadership and Corporate Culture are instrumental to develop the interactions with the environment in different ways.

All the above elements should be intentionally designed keeping in mind the ecosystem in which we want to operate, keeping in mind that our interactions with the external actors of the ecosystem will always be marked by a coexistence of emergence and intentionality.

What is interesting is that within an ecosystem, the concepts of casuality and intentionality get amplified by the number of interactions with autonomous organisms, up to the point that we can trace full coesistence of the two. We can also speak of circular causality (via autocatalysis) and emergent intentionality (via multiscale nonlinear interactions) (Spivey, 2013): these seem to be almost two oxymorons, that however help us understand the way ecosystem react to our design efforts.

In simple words, as an organisation you can try to shape the ecosystem through your own design tools, applying intentionality in the definition of any of the elements cited above. However, the moment you initiate interactions with the system, you will receive inputs affecting your own design. These feedback loops create two interesting phenomena, as mentioned.

- circual causality is a phenomena that is present in different natural sciences, and basically is a process by which A causes B, and B causes A in return. There are multiple instances for this in nature, and are often processes that allow for self-preservation of a system. Think of a pendulum as a visual example. From an organisation design perspective this means thinking in terms of the effects of unintentional actions. A lot of the current discourse on environmental sustainability looks at these phenomena for example.

- emergent intentionality is also a phenomena that is present in nature, whereby A suppress or reinforce B. It is a phenomena often traced in meteorology, whereby some patterns (called nonlinear interactions) do not allow to predict the outcome, as they can be completely opposing results. Translated in organisation terms, this is what happens when multiple independent organisations within an ecosystem, act consistently, letting a new trend emerge.

These are just two examples of what makes ecosystem design a complex matter. Very few organisations have the power to create their own ecosystem. Most can only have a limited impact on the environment they play with. But each choice they take, from the identification of customers, to the interaction with stakeholders, needs to be aligned and consistently designed.

A truly intentional organisation is capable to reach a mutually enriching pattern of relationships with its ecosystem, beyond individual sustainability, allowing the entire ecosystem to thrive.

Summing Up

As I approached this article, I thought I would be happy about terminating the series I had started more than one year go. The reality, is that I have opened more doors to even a different understanding of what I had already written. Why? Because fully respecting the idea of General Systems Theory applied here, and the different levels of organisation, it is clear that every organisation can be analysed as an organism, but also as an ecosystem of its composing parts. Which calls then for interrogating myself to what are the effects of this reasoning towards the framework I have developed to ma an organisation? Should I also consider the relationship between the OEF components as an ecosystem?

As you saw, I opted for the second, trying to give a glimpse at how Ecosystem influence all other components (and are somewhat the product of the other elements of the system). This, however, brings new insights into how I approached the rest of the series that probably I need to take into account in a new re-edition of this work.

This said, I think it is clear for all that we cannot think in terms of organisations separated from their ecosystem.

Introducing the Organisation Evolution Framework

Visual representation of Organisation Design building blocks and their dynamic relationships.

Now released in Version 2, open for feedback.

Again, feel free to give feedback, and suggest any article or model that I might be missing in this article, using the comment section below. Thank you!

Reference List

Adner, R. (2016). Ecosystem as Structure. Journal of Management, 43(1), pp.39–58.

Coase, R.H. (1937). The Nature of the Firm. Economica, [online] 4(16), pp.386–405. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1468-0335.1937.tb00002.x [Accessed 13 Dec. 2021].

Donaldson, T. and Preston, L.E. (1995). The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications. The Academy of Management Review, 20(1), pp.65–91.

Droege, S.B. (2008). Stakeholders – organization, levels, business, Stakeholder perspective. [online] http://www.referenceforbusiness.com. Available at: https://www.referenceforbusiness.com/management/Sc-Str/Stakeholders.html [Accessed 14 Dec. 2021].

Freeman, R.E. (1984). Strategic Management : a Stakeholder Approach. Boston: Pitman.

Freeman, R.E.E. and McVea, J. (1984). A Stakeholder Approach to Strategic Management. SSRN Electronic Journal. [online] Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228320877_A_Stakeholder_Approach_to_Strategic_Management.

Granstrand, O. and Holgersson, M. (2020). Innovation ecosystems: A conceptual review and a new definition. Technovation, 90-91, p.102098.

Iansiti, M. and Levien, R. (2004). The keystone advantage : what the new dynamics of business ecosystems mean for strategy, innovation, and sustainability. Boston, Ma: Harvard Business School Press, Cop.

Jacobides, M.G., Cennamo, C. and Gawer, A. (2018). Towards a theory of ecosystems. Strategic Management Journal, 39(8), pp.2255–2276.

Linde, L., Sjödin, D., Parida, V. and Wincent, J. (2021). Dynamic capabilities for ecosystem orchestration A capability-based framework for smart city innovation initiatives. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 166, p.120614.

Mars, M.M. and Bronstein, J.L. (2017). The Promise of the Organizational Ecosystem Metaphor: An Argument for Biological Rigor. Journal of Management Inquiry, 27(4), pp.382–391.

Mars, M.M., Bronstein, J.L. and Lusch, R.F. (2012). The value of a metaphor: Organizations and ecosystems. Organizational Dynamics, 41(4), pp.271–280.

Moore, J.F. (1996). The death of competition : leadership and strategy in the age of business ecosystems. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Moore, J.F. (2006). Business Ecosystems and the View from the Firm. The Antitrust Bulletin, 51(1), pp.31–75.

Rabinowitz, P. (2018). Chapter 7. Encouraging Involvement in Community Work | Section 8. Identifying and Analyzing Stakeholders and Their Interests | Main Section | Community Tool Box. [online] Ku.edu. Available at: https://ctb.ku.edu/en/table-of-contents/participation/encouraging-involvement/identify-stakeholders/main [Accessed 14 Dec. 2021].

Ramenskaya, L.A. (2019). OVERVIEW OF APPROACHES TO RESEARCH OF BUSINESS ECOSYSTEMS. Вестник Алтайской академии экономики и права, 2(№12 2019), pp.153–158.

Spivey, M.J. (2013). The Emergence of Intentionality. Ecological Psychology, 25(3), pp.233–239.

Valkokari, K. (2015). Business, Innovation, and Knowledge Ecosystems: How They Differ and How to Survive and Thrive within Them. Technology Innovation Management Review, [online] 5(8). Available at: https://timreview.ca/article/919 [Accessed 15 Dec. 2021].

Walker, D.H.T., Bourne, L.M. and Shelley, A. (2008). Influence, stakeholder mapping and visualization. Construction Management and Economics, 26(6), pp.645–658.

World Bank (2005). What is Stakeholder Analysis? [online] Available at: http://www1.worldbank.org/publicsector/anticorrupt/PoliticalEconomy/PDFVersion.pdf [Accessed 14 Dec. 2021].

Cover Photo by Sebastian Pena Lambarri on Unsplash

[…] Organisation Ecosystem: The Theory and the Practice […]

Kudos to great and informative content but the structure of this site is a mess. I would love to dig through everything but since you have not put any real effort into making that easy – I will not. To bad.

Happy to get feedback on the structure of the website:)

[…] Adopt an outside-in perspective, understanding customers and critical stakeholders in your design. This means moving away from the idea that the environment is simply an external factor, moving entirely into an Ecosystem logic. […]