- What is Organisation Design?

- Introducing the Organisation Evolution Framework

- Consistency and Intentional Design. Building the Organisation of the Future.

- Building the Intentional Organisation

- Business Models: the theory and practice

- Strategy Frameworks: The Theory and the Practice

- Organisation Models: a Reasoned List between Old and New

- Operating Models: the theory and the practice.

- Leadership Models: The Theory and the Practice

- Purpose: The Theory and the Practice

- Corporate Culture: The Theory and the Practice

- Organisation Ecosystem: The Theory and the Practice

Strategy is a critical element for Organisation Design and the second foundational block of the Organisation Evolution Framework. It is a required component to do business (any business). It is strictly linked to the Business Model definition and is required to allow its translation into practice through the organisation Operating Model. I already wrote an article a few months ago titled What is Corporate Strategy, in which I interrogated on the meanings of this topic. I’ve now merged its content into this article, to ensure a centralized view on the subject. Back then, the piece was triggered by reading the book As I read the book The Passion Economy by Adam Davidson.

First of all, the topic itself is not that old. Strategy had always been a military concept, sometimes applied to Diplomacy and Politics, but never really to the business. Let’s look at Google’s NGram viewer, and see the usage of the term Corporate Strategy across millions of books. The word appears only after 1960 and becomes common only after 1980. For sure, the appearance of Michael Porter‘s article How Competitive Forces Shape Strategy in 1979 and the subsequent 1980 book Competitive Strategy have had their influence.

Porter’s book, as well as much of the research that followed, concentrated on the concerns of large businesses. For many years still, Strategy was something that large companies (often supported by specialised consulting companies) did.

Strategy was more akin to some form of mystical shamanism than it was to a learnable business tool.

Adam Davidson, The Passion Economy, page 20 (Davidson, 2020)

Article Updates: this post was updated after its original publication.

– May 3rd, 2020: Added Sun Tzu’s Art of War, the OODA Model and the Wardley Map. Updated References and corrected a few typos.

Defining Strategy

Defining Strategy is not an easy task. The concept has been borrowed from the military and adapted for use in business contexts. In business, as in the military, strategy bridges the gap between policy and tactics. (Nickols, 2012). Which already starts adding a complexity: what is the difference between Strategy and Tactics?

The essence of strategy is choosing to perform activities differently than rivals do.

Michael E. Porter, What is Strategy?, (1996)

There are many different definitions of Strategy. In his foundation study, (that I have recently reviewed) Alfred Chandler (1969) defines Strategy as the determinator of the basic long-term goals of an enterprise, and the adoption of courses of action and the allocation of resources necessary for carrying out these goals. In 1979 George Steiner wrote a book titled Strategic Planning which interestingly appeared as the “bible” of Strategic Planning process precisely in the period where this concept started to fade away, hit by the petrol crisis. In the book, the author lists several definitions for Strategy:

- Strategy is that which top management does that is of great importance to the organization.

- Strategy refers to fundamental directional decisions, that is, to purposes and missions.

- Strategy consists of the essential actions necessary to realize these directions.

- Strategy answers the question: What should the organization be doing?

- Strategy answers the question: What are the ends we seek, and how should we achieve them? (Steiner, 1979)

He fails to add a definition of its own but allows to give a view of the complexity of the subject.

Around the same period, Herny Mintzberg (1979) talks about Strategy as the mediating force between the organization and its environment: consistent patterns in streams of organizational decisions to deal with the environment. He later wrote a book that is a pillar in understanding the multiple views of what Strategy.

More recently, some other definitions developed more the focus on Value. I find the meaning used by Michael E. Raynor to be particularly useful: how an organisation creates and captures value in a specific product-market (Raynor, 2007).

This definition has the advantage of helping to define three elements:

- You need to identify the Organisation.

- You need to identify the Product Market in which the Organisation operates.

- You need to determine what value it creates (and be able to measure it).

The points above may seem trivial but are the core of how to define the exact sense of the existence of an organisation. Any organisation.

When I taught Strategic Management of Non-Profit Organisations at the University of Bologna, the question about Strategy was put precisely in that sense. Those elements are present for any Organisation. Businesses are usually focused on revenues and profits in terms of Value Creation. But this is not necessarily the only Value created. Any non-Profit organisation still operates in a specific Product market (those who fail to recognise this, tend to become irrelevant quickly).

The binding element of the answers to the three questions needs to be The Purpose that an organisation has. We have already discussed this. But Purpose and Strategy are not the same.

Mintzberg Classical Strategy Typologies

Henry Mintzberg described five definitions of strategy in a 1987 article and later expanded his classification in his seminal book Strategy Safari in 1998 (Mintzberg, Lampel and Ahlstrand, 1998).

- Strategy as a plan – a directed course of action to achieve an intended set of goals; similar to the strategic planning concept;

- Strategy as a pattern – a consistent pattern of past behaviour, with a strategy realized over time rather than planned or intended. Where the recognised pattern was different from the intent, he referred to the strategy as emergent;

- Strategy as a position – locating brands, products, or companies within the market, based on the conceptual framework of consumers or other stakeholders; a strategy determined primarily by factors outside the firm;

- Strategy as a ploy – a specific manoeuvre intended to outwit a competitor; and

- Strategy as a perspective – executing strategy based on a “theory of the business” or natural extension of the mindset or ideological perspective of the organization.

What is Strategy then?

Are all these definitions correct? Probably yes, which adds to the complexity of the problem.

What, then, is strategy? Is it a plan? Does it refer to how we will obtain the ends we seek? Is it a position taken? Just as military forces might take the high ground prior to engaging the enemy, might a business take the position of low-cost provider? Or does strategy refer to perspective, to the view one takes of matters, and to the purposes, directions, decisions and actions stemming from this view? Lastly, does strategy refer to a pattern in our decisions and actions? For example, does repeatedly copying a competitor’s new product offerings signal a “me too” strategy? Just what is strategy?

Strategy is all these—it is perspective, position, plan, and pattern. Strategy is the bridge between policy or high-order goals on the one hand and tactics or concrete actions on the other. Strategy and tactics together straddle the gap between ends and means. (Nickols, 2012)

I tend to agree with this point of view. Strategy is not about setting the Purpose, nor establishing the Goals. Instead, it is about getting there, bridging the gap between current means and the end we want to reach.

Generating Value and Managing Uncertainty

Strategy is also not a plan, which is also essential to understand. Too many organisations limit their interpretation of the Strategy to the Strategic Plan they create every few years. That part is the Execution of the Strategy, a significant factor for sure, but is not the same. Another typical confusion for some is the identification of Corporate Strategy with the way the Organisation is designed. Organisation Charts alone don’t tell the real story, and again the risk is that we mix Execution with the way we develop the real Strategy.

The truth is that a successful Organisation Strategy is a somewhat fascinating mix between two seemingly opposite elements: Value Generation and Management of Uncertainty. This is especially true as we address an era where change seems to be continually accelerating.

Many tools exist that can help create identify the right mix. Along with a structured mindset that understands that Strategy Definition needs to be a circular process, capable of continually reviewing itself through a feedback loop. Insight, Foresight and Intuition are still critical components for the definition of a valid Strategy. Yet, so it is Flexibility and the capacity to review it and update it over time.

This eventually scopes the concept of Strategy in establishing priorities for the organisation to do that correctly: generate Value and Manage uncertainty over some time to reach a specific end.

Strategy Frameworks: a reasoned list

Over time several Strategy Frameworks have been developed around the world both by scholars and consulting companies. A few notable frameworks have also been established by large corporations, and have then been adopted by outsiders.

A consequence of the difficulty in defining what Strategies are, also means that there are many different Strategy frameworks out there, often with different expectations. Often, companies use one or more of these approaches jointly, and in many cases, each company has adjusted these tools to their internal processes.

We can, however, identify at least five groupings of tools:

- Choice Tools. These are frameworks that are used by companies to make choices. As such, they usually consist of a structured analytical process to prioritize and take decisions. A prime example of these is the SWOT analysis. Most of these frameworks can be used in many different scenarios, thus are not unique to Strategy Definition.

- Market Analysis Tools. These are frameworks that are used to analyse the current shape of the market or the ecosystem in which the company acts: the definition of the strategy will, therefore, result in the Positioning of the company within that market. Porter has been a great innovator in this area. One word of caution, often the result of using these frameworks can also have an impact on the Business Model of the organisation.

- Internal Analysis Tools. These frameworks are instead looking inside the organisation and try to help to shape the organisation strategy in terms of capabilities and internal value creation. We can see an overlap between these tools and the definition of the Operating Model of an organisation. Still, it is essential to name a few here, as there nevertheless needs to be a secure connection between Strategy and Execution.

- Portfolio Management Tools. These are frameworks that look at how to position individual services and products not only compared to the market but also compared to each other. Some of these frameworks might apply to entire business units. A prime example of these is the BCG Matrix.

- Strategic Planning Tools. These are frameworks that try to establish a path to achieve a specific strategic objective. As illustrated in the definition section above, the definition of the goal itself is not part of a Strategy, however many of these tools also consider this piece as part of their process. An example of tools in this is Scenario Planning.

I will use these working definition to structure the rest of this post. Please note: I’ve decided not to include into this article the models that focus on Strategy Execution. Although they have had impacted a lot the way many companies have been looking at Strategy, frameworks such as Management By Objectives, the Balanced Scorecards or OKRs are not tools to frame and develop a strategy, but rather to follow up in its execution (thus should more formally belong to the Operating Model of a company).

Choice and Priorities Strategy Frameworks

As mentioned, these tools are in its most straightforward form frameworks to facilitate prioritization and choices. As such, they are perfectly adhering to the definition of Strategy I suggested as part of the Organisation Evolution Framework.

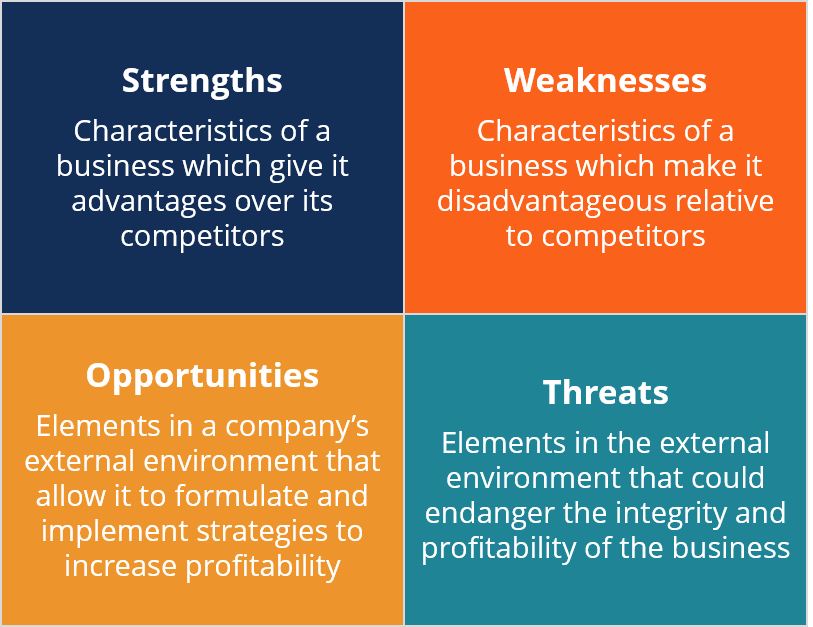

SWOT Analysis

A SWOT Analysis is one of the most commonly used tools to assess the internal and external environments of a company and can be part of the definition of a strategy. The origin of the tool are uncertain, but today is one of the most widely used tools to get an understanding of a specific business (but can also be used on a product or service), as it balances an internal and external view. SWOT is today a very flexible tool that can also be applied to a place, and the entire industry, even a person. It is a tool that helps decision making, and it introduces opportunities to the company as a forward-looking bridge to generating strategic alternatives.

SWOT is an acronym for Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats. The first two elements are related to internal factors, while the other two refer to external elements.

A specific framework looks at adding Strategy to the model, creating SWOT+S (Savkin, 2019).

PEST Analysis

A PEST analysis (also now known as PESTEL or PESTLE (de Bruin, 2018)) is a framework used to analyse and monitor the macro-environmental factors that may have an impact on an organisation’s performance. This tool is especially useful when starting a new business or entering a foreign market, as it clarifies the specific situation. As a Strategy Definition tool is often used in conjunction with other frameworks.

The acronym stands for Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Environmental and Legal factors. Through the years, more models have emerged that have added other dimensions, such as Demographics, Regulatory, Ethics etc. (Wikipedia Contributors, 2019a).

The model itself is a straightforward and intuitive tool to understand the trends in your business environment, as it allows us to understand also the changes in the landscape and how they might affect your organisation positioning.

Even the origins of this model are not fully known, as variations of it has been used since the fifties in military and organisational contexts.

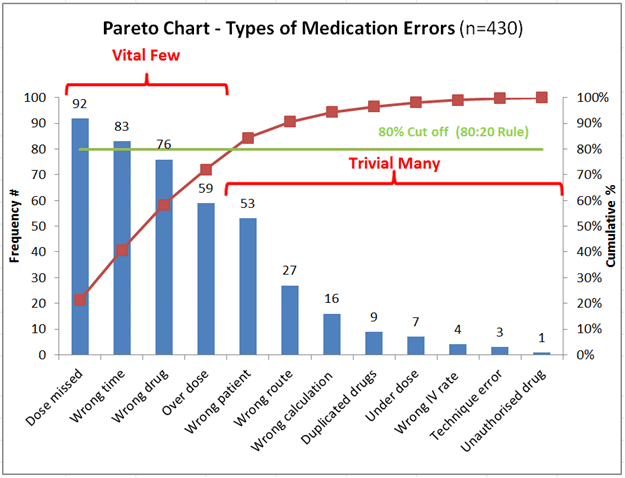

Pareto Analysis

Pareto analysis is a problem-solving technique useful where many possible courses of action are competing for attention. In essence, the problem-solver estimates the benefit delivered by each step, then selects a number of the most effective measures that provide a total benefit reasonably close to the maximal possible one. The analysis often uses a so-called “Pareto Chart”, which visually illustrates the distribution of the issues, and allows for prioritisation.

The Pareto Analysis is heavily dependent on the so-called 80/20 Rule (also known as the Pareto principle or the law of the vital few & trivial many) states that, for many events, roughly 80% of the effects come from 20% of the causes. Joseph Juran (a well regarded Quality Management consultant) suggested the principle and named it after the Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto, who noted the 80/20 connection in 1896. Vilfredo Pareto showed that approximately 80% of the land in Italy was owned by 20% of the population. Pareto also observed that 20% of the peapods in his garden contained 80% of the peas. According to the Pareto Principle, in any group of things that contribute to a common effect, a relatively few contributors account for the majority of the impact (Six Sigma Daily, 2018). For example, it is commonly found that 80% of complaints come from 20% of customers and 80% of sales come from 20% of clients

The ordering in a Pareto Chart helps identify the ‘vital few’ (the factors that warrant the most attention, i.e. factors whose cumulative per cent (dots) fall under the 80% cut-off line) from the ‘trivial many‘ (factors that, while useful to know about, have a relatively smaller effect, i.e. cumulative per cent dots that fall above the 80% cut-off line).

Using a Pareto Diagram helps to establish priorities. In a strategy context, it can, for example, allow choosing on which products to concentrate efforts, which business lines, which areas to outsource etc.

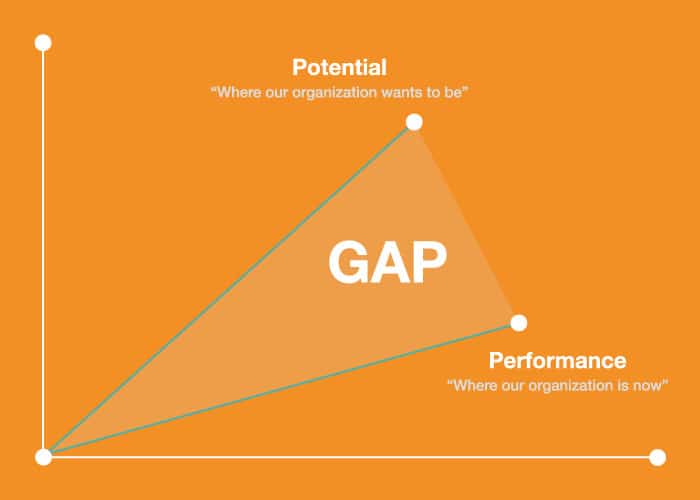

Gap Analysis

Gap Analysis is another tool that is often used in the context of Strategy Definition (often in conjunction with other tools). The idea of “Gap Analysis” comes from the concept of confronting a current performance status (either actual or projected in the future) and a “potential” state. Once the Gap is identified, it is possible to then look at ways to fill the gap with specific strategic options.

“Bridging the Gap” becomes, therefore, the expression to fulfil the difference between AS-IS and TO-BE. Which is why this concept is often used in Change Management programmes.

Market Analysis Strategy Frameworks

These frameworks are focused on the evaluation of the external factors that impact on the position of the organisation in a market and are therefore used to help shape the strategy as a Positioning within a market.

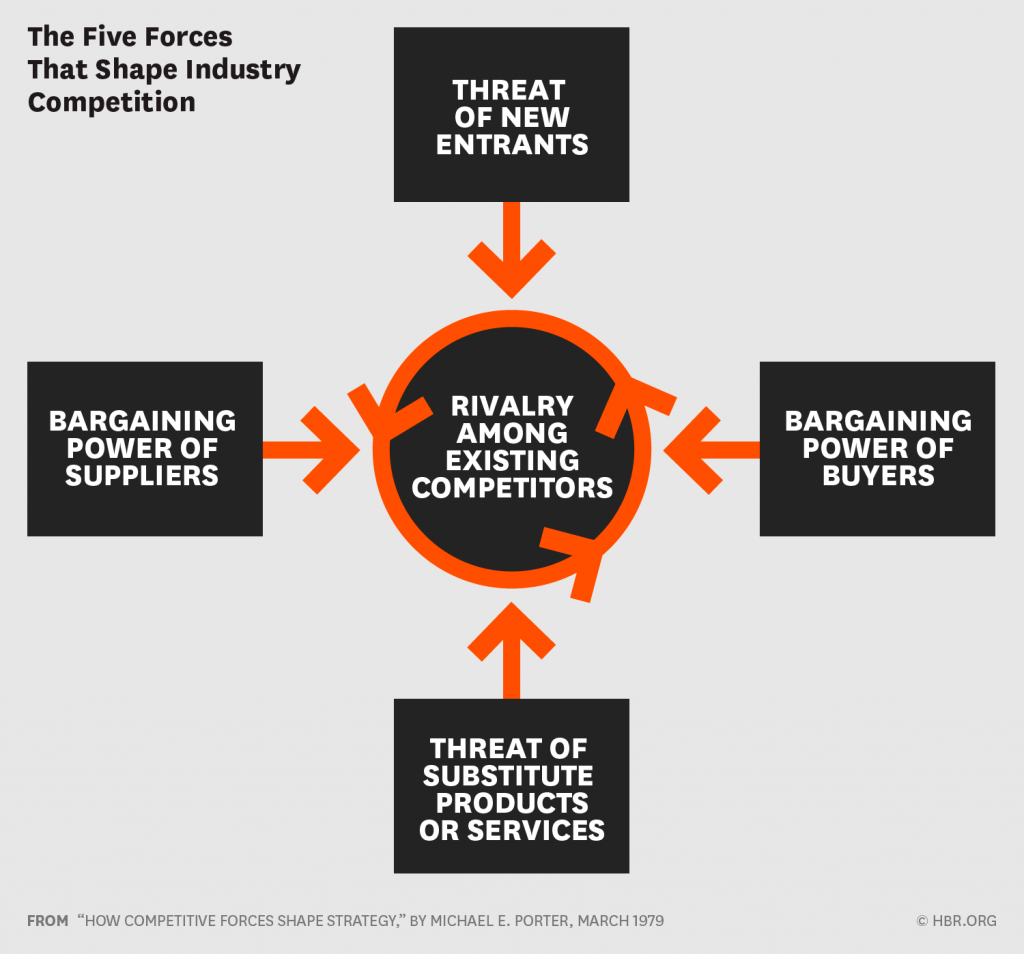

Michael Porter’s Five Forces

Porter’s Five Forces analysis is a framework that helps to analyze the level of competition within a specific industry, and thus framing the Strategy of a particular company venturing in that area. Michael Porter introduced a clear distinction between Strategy and Operational Effectiveness, in the sense that he clarified that performing similar activities better than rivals is not a Strategy (Porter, 1996). According to Porter, a company can only outperform competitors if it can establish a difference that it can preserve. This is where strategy comes in. Strategic positioning is about performing different activities from rivals and combining them in such a way that they deliver a unique mix of values. Which is why in his model, he clarifies that competitiveness does not depend only from competitors.

The state of competition in an industry depends on five primary forces (Porter, 2008):

- Competitive rivalry

- The threat of substitute products

- Bargaining power of buyers

- The threat of new entrants

- Bargaining power of suppliers

The collective strength of these forces determines the profit potential of an industry and thus its attractiveness. When all five forces are very intense, almost no company in the industry earns an attractive return on investment. When the forces are milder, there is instead room for higher returns.

In Porter’s Model Strategy is, therefore, about the Positioning within an industry, balancing the profit potential with its balance against the market-shaping forces.

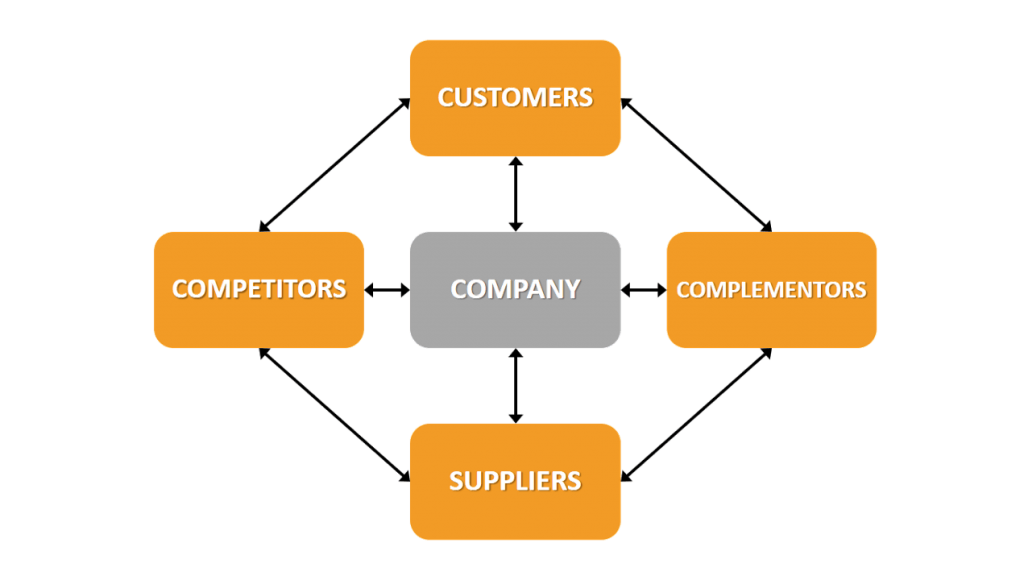

Value Net Model

The Value Net Model is an alternative to Porter’s Five Forces. However, it recognises the importance of not just of competitions strategies, but also of cooperation ones. Proposed by Adam M. Brandenburger and Barry J. Nalebuff in their 1996 book Co-opetition, the model offers integration of elements of game theory in the context of business strategy. Primarily they explain that Porter’s model has focused too much on the competition side, and thus misses on the collaboration potential of an industry.

The four components of the model are:

- Customers

- Suppliers

- Competitors

- Complementors.

The concept of Competitors entails all three types of “rivals” of the Porter model. The newly introduced concept is that of Complementors. These are not necessarily former partners, but constitute the number of organisations that provide products and services that can work well with what your organisation produces, so that they give an overall better experience to the customer. Adding this Sixth Force to the mapping of the environment allows having a much better view of the market, and the possibility to integrate into existing ecosystems.

The Strategic Sweet Spot

The Strategic Sweet Spot (Collis and Rukstad, 2008) is an evolution of Porter’s Five Forces framework. It involves the identification and usage of your company’s capabilities to satisfy customer needs in ways that competitors would have the most difficulty emulating.

To use this framework, you’ll want to ask yourself these questions:

- What core competencies does your company have that your competitors do not? Which of those core competencies are hardest to emulate and develop from the position of your competitors?

- What is some customer needs that your company is in a better place to serve than your competitors?

Defining the Sweet Spot is, therefore, the core of this strategy, which joins an internal view (capability) with an external element (understanding of the external market and customer needs).

Internal Analysis Strategy Frameworks

These tools look more to the internal capabilities of the companies rather than the external market. This can be the result of an alternative way of seeing organisations, focused on internal resources, or only at the necessity to prioritize interior choices.

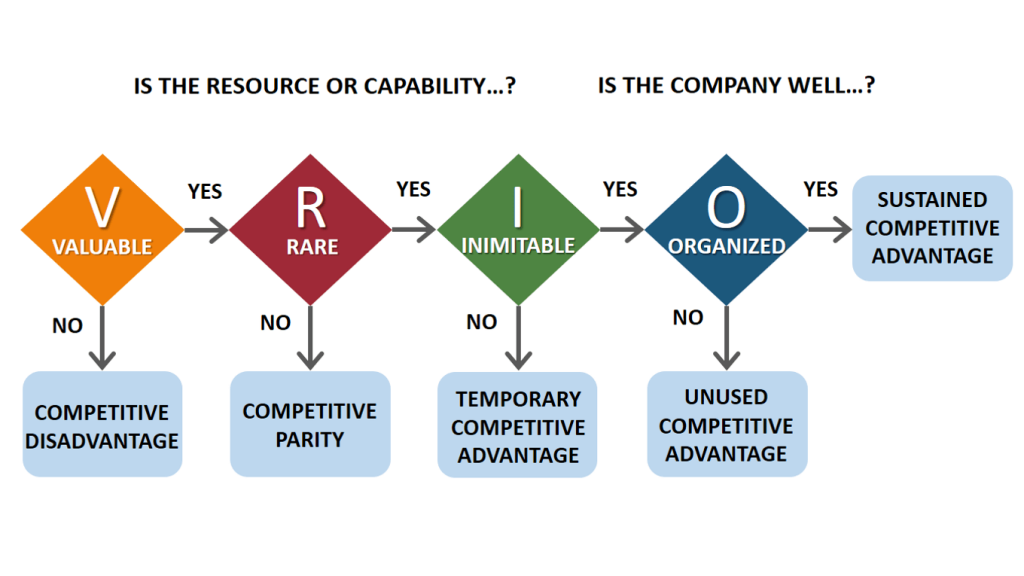

VRIO Analysis

The VRIO Analysis or VRIO Model is part of a broader framework of business understanding, elaborated in 1991 by Jay Barney and called Resource-Based View (RBV). The framework focuses on the examination of the link between a company’s internal characteristics and its performance. It, therefore, proves an alternative view versus those models (like Porter’s Five Forces), that instead mainly look externally to understand a company’s profitability. The supporters of RBV argue that organizations should look inside the company to find the sources of competitive advantage instead of looking at the competitive environment. The key concepts within this view are, therefore, Firm Resources and Sustainable Competitive Advantage (Wernerfelt, 1995). Resources are defined as all assets, capabilities, organizational processes, firm attributes, information and knowledge controlled by a firm that enables it to improve its efficiency and effectiveness (Barney, 1991) and can be both Tangible and Intangible.

The link between the resources and the source of competitive advantage is what the VRIO analysis aims to do. It identifies the attributes that internal resources need to have to provide a competitive edge, and the model is framed in four key questions. Is the resource:

- Valuable: If support can help find opportunities or defend against threats, it can be considered relevant. Moreover, a valuable resource should help increase customer value.

- Rare: If a resource can only be acquired by one or a few companies, it is considered rare. A resource that is valuable and rare will provide a significant competitive advantage.

- Costly to Imitate: If other organizations that don’t have the resource can’t imitate it, buy it or find a substitute for it at a reasonable price, that resource is considered costly to imitate.

and is the company well…

- Organized to capture value: The organization should have processes, policies, and systems in place to capture the value created by valuable, rare and costly to imitate resources.

From a Strategy Perspective, this Framework provided for the first time an analysis tool to evaluate and prioritize internal resources, rather than focusing exclusively on the external factors. Used in conjunction with other models, it allows considering internal capabilities first, providing a useful model for all those markets that are at their initial development stage.

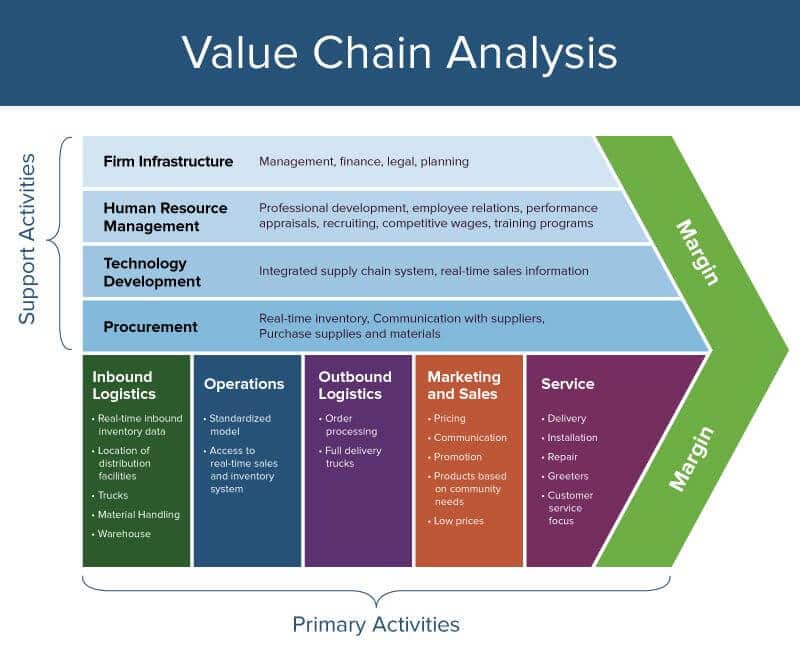

Porter’s Value Chain Analysis

Another essential framework from Porter is the Value Chain Analysis. In essence, the model focuses on the Value creation that the individual activities provide to the end-customer (which in Porter’s view is measured in terms of the Margins that the organisation can establish).

This tool is often associated with the definition Strategies; however, as we’ve seen, Value Chains are somewhat related to the way the organisation Operates, thus should be encompassed in the Operating Model. However, used in conjunction with other tools, the Value Chain Analysis can be a useful feedback mechanism to adapt the strategy based on the current Operating Model and identify priorities for the next strategy cycle.

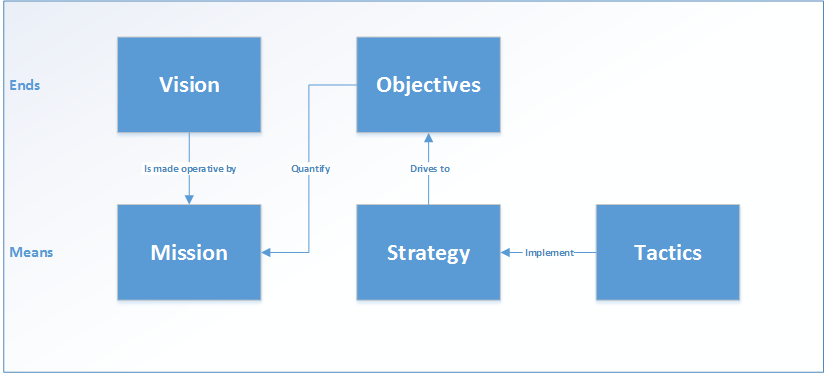

VMOST Analysis

Developed by Rakesh Sondhi in his 1999 book Total Strategy, this analysis model is meant to complement a PESTEL analysis (that is focused on the external environment). It focuses on a sort of Strategic Review of the organisation by looking at the critical components of the organisation strategic intent: Vision, Mission, Objectives, Strategy and Tactics. The idea is that only by translating a Strategy into its five elements, and ensuring that all of these are relevant for their stakeholders, a company can succeed.

Born as an analysis tool, it is often referenced in the development of Strategy, as it allows to crystallize the elements in a formalised way and ensure that Strategy is fully aligned in terms of its composing features (Olson, 2018).

Portfolio Management Strategy Frameworks

These are tools that focus mainly on the management of a product or service portfolio. As the business grows, some of these can be applied to entire business units, looking at the positioning of each within its reference market.

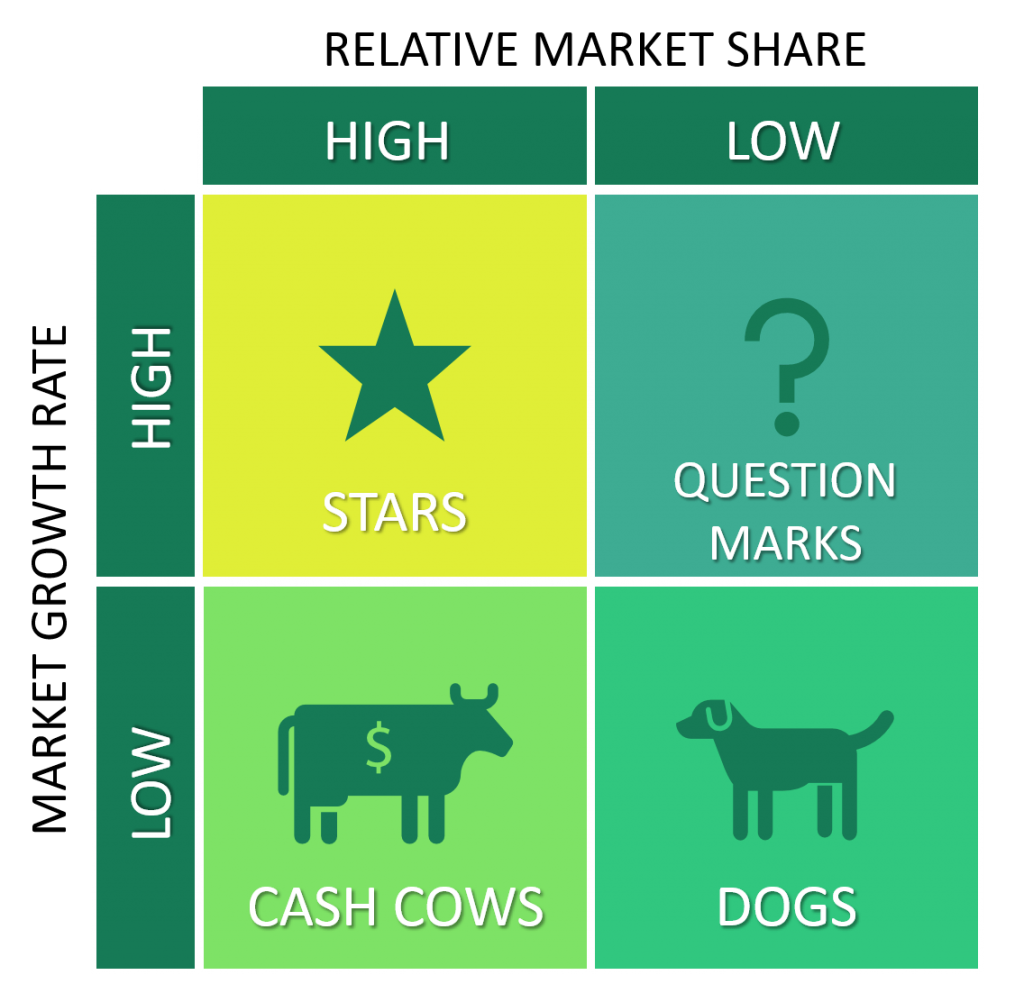

BCG Matrix

The Boston Consulting Group’s product portfolio matrix (also known as BCG Growth-Share Matrix or more simply BCG Matrix) is designed to help companies consider growth opportunities by reviewing their portfolio of products or business units in order prioritize investments. (Henderson, 1970) As such, this model can be defined as a Portfolio Management Framework.

The matrix is divided into four quadrants based on two factors:

- Market growth – how well the product is growing when compared to other products?

- Market share – what is the size of the market the product has captured compare to the competition?

The crossing of these creates four quadrants, using names that are today very common in the business jargon.

- Star (high share and high growth): Products that belong to this category have a rapid growth rate and a dominant market share. They generate much cash as well as require much investment to ensure that they maintain their position. If they can keep their high status, they will eventually become ‘cash cows’.

- Cash cow (high share and low growth): These are the products that are most profitable to a business. They don’t cost much for the company to maintain and generate a significant amount of income. The cash gained from them should be invested in the Star products to help them grow further.

- Dogs (low share low growth): Products that have a small market share and operates in a slowly growing market. Since they generally generate low or negative returns and drain resources, investing in them is not worth it.

- Question marks (high growth, small share): The future of the products that belong to this category is uncertain; as they have a low market share in a fast-growing market. It has the potential to become a Star by gaining market share, but it also has the potential to become Dogs by failing to gain market share. It’s essential to keep a close eye on these.

Most products start as a Question Mark, with relatively small market share and a high growth market potential. Depending on how well the market goes, they might become a Star or a Dog. Ultimately the product could become a cash cow, which allows to “milk” revenues to fund other products.

The model enables creating a Strategy in terms of Portfolio, ensuring that your products and services are spread across the matrix.

Ansoff Matrix

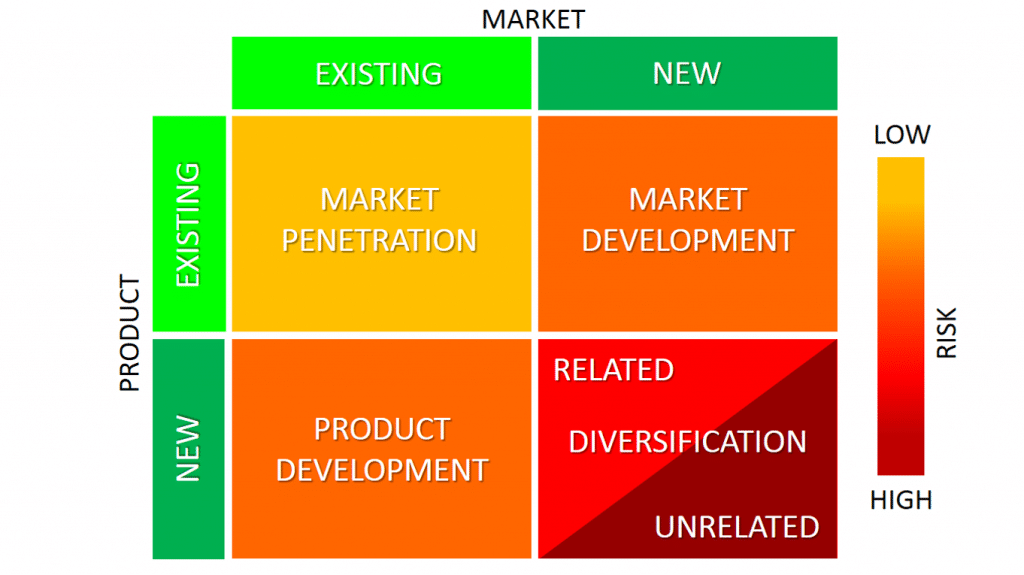

The Ansoff Matrix is a classical tool that looks at Diversification. Igor Ansoff published an article in 1957 focused on Strategies for Diversification, where he suggested a matrix to differentiate strategies based on products and markets. Also known as Product/Market Expansion Grid) can allow to quickly summarize the potential of different strategies and the risk associated.

According to the matrix, there are two ways that Strategy can be implemented:

- By varying what is sold (product growth)

- By varying whom it is sold to (market growth)

Accordingly, the matrix delivers four strategic options that have different levels of risks;

- Market penetration: This strategic option focuses on selling existing products to the company’s existing market. It’s the one with the lowest uncertainty as the company already knows its customers and has channels already established to reach them. Here the company can decrease prices and offer discounts to attract customers.

- Product development: This is where the company develops new products for its existing market. To make it work, the company has to rely on extensive research and provide innovative solutions to meet the needs of the customers.

- Market development: Here, the company can market its existing products to a new market. A new market may entail new geographies, different customer segments, new channels, needs, etc. It’s riskier than the other two strategies as it deals with a new market.

- Diversification: Here, the company develops new products for a new market. This is the riskiest strategy of all four. However, the risk can be mitigated through related diversification (a new product that is related to the existing product) and unrelated diversification (a new product that is not related to the current product).

This matrix has somehow anticipated both the BCG one as well as some of the principles of Porter’s model (in allowing to look at understanding how an organisation strategy interacts with the market).

Porter’s Generic Strategies

In his 1985 book Competitive Advantage, Michael Porter introduced the concept of Generic Strategies as a way for organisations to position themselves between their rivals. He identifies three generic strategies:

- Cost Leadership

- Differentiation

- Focus.

The choice is linked to two dimensions. On one side, a company can decide to opt for two types of competitive advantage: either by going low cost or by creating differentiation by looking at dimensions that are valued by customers. On the other side, the company can choose between two types of scope, either focusing on a specific market niche or opting for the broader market. Combined together, these strategies offer four potential ways to position yourself about competitors. Trying to excel in all four strategies will eventually lead to becoming “stuck in the middle” as Porter defined (Porter, 1985).

Although some have questioned the fact that these are the only strategies available, this model is still used to determine the positioning of a business within a market, but can also be used at the level of a Product, Service and Business Unit. Which is why I have classified it into this category.

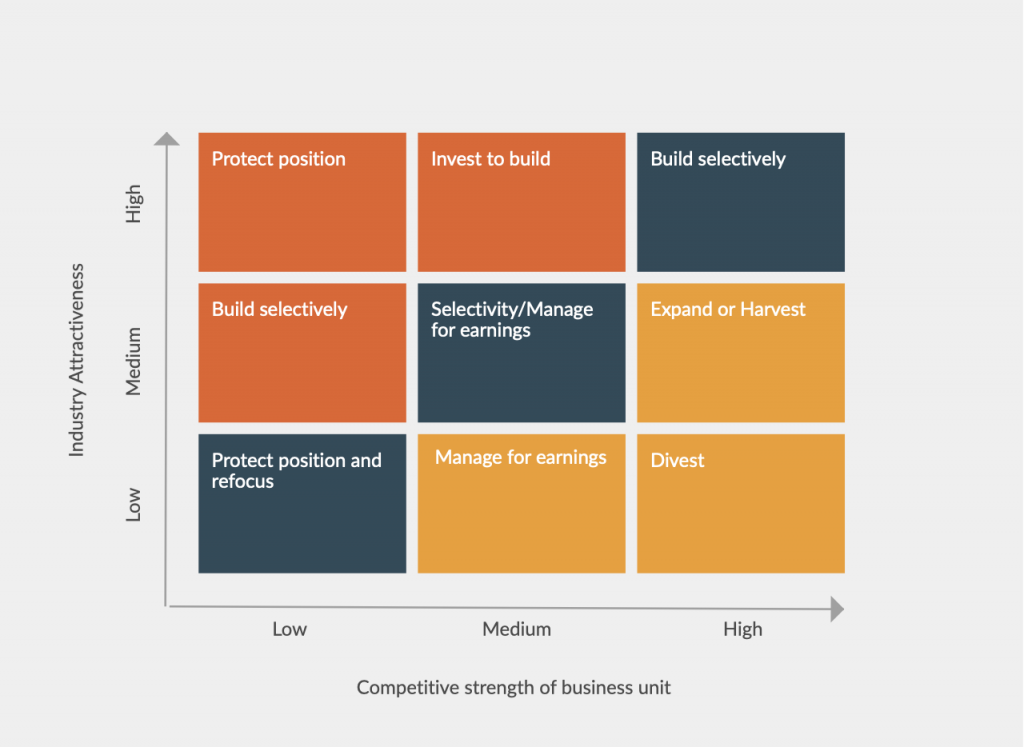

GE-McKinsey Nine-Box Matrix

The GE-McKinsey nine-box matrix (McKinsey, 2008) offers a systematic approach for the decentralized corporation to determine where best to invest its cash. Developed specifically for a large group such as General Electric, rather than relying solely on each business unit’s projections of its prospects, the company can evaluate all its units by two factors that will determine whether it’s going to do well in the future: the attractiveness of the relevant industry and the unit’s competitive strength within that industry. As such, this tool is effectively a Portfolio Management framework focused on Business Units rather than individual products or services.

Multi-business corporations can use it to evaluate their different business units and prioritize investments among them systematically., as well as to choose where and when to divest in a particular industry, and when and where to choose to enter a nee business.

The matrix is organised across two axes, each arranged in three gradients: High, Medium and Low.

- Market or Industry Attractiveness

- Competitive Strength of the Business Unit.

The matrix delivers a mix of actions, which can be broadly grouped into three categories:

- Build and Invest: these are the areas (orange in the figure) that are medium to high in terms of industry attractiveness and lower in terms of competitive strengths. It’s the areas where the company should prioritize investments.

- Manage: these are the areas (blue in the figure) where the company should focus on managing current positions.

- Harvest/Divest: these are the areas (yellow in the figure) where the company should harvest the results obtained, also considering divestitures.

Strategic Planning Frameworks

These frameworks provide a toolkit not just for the analysis of the current environment and the identification of options, but actually create a full process for the definition of the Strategy. I am using the term “strategic planning” in its widest sense, although I will be detailing it also as a specific method.

Strategic Planning

In the 1970s, many large firms adopted a formalised top-down process denominated Strategic Planning Under this process, Strategy becomes a deliberate outcome of a top-down approach in which business leaders would periodically formulate the firm’s strategy, then communicate it down for implementation.

The model (of which the figure here on the side represents the traditional basic steps), was often more concerned in the cascading of the objectives, rather than the specific definition of a strategy to attain them (Steiner, 1979).

Born in a historic period of high predictability, the model worked until market conditions and environmental volatility started to increase.

Interestingly, the methodology reached its apex at the end of 1979, exactly when it was evident that a monolithic process, which was not taking into consideration different scenarios, was meant to fail. The model showed to be not suited only for stable environments, showing not to be responsive enough for competitive situations.,

In times of change, some of the most successful strategies might emerge at lower levels of the organisation, but this model would fail in considering them completely. Moreover, its reliance on accurate forecasting, does not take into account unexpected events.

Which is why this model has been superseded by more flexible and inclusive models of definition of the Strategy.

Sun Tzu’s Art of War

When talking about Strategy, we cannot avoid considering the contribution of Sun Tzu and his Art of War. I will dedicate a more complete article on his teaching but wanted to point out how the Five Factors he lists on his work, are a great tool to perform a Strategic Analysis. The below figure represents the five factors.

Of course, we need to add a very contemporary reading and interpretation to his teachings. Despite being one of the mos read books on the topic of Strategy, it has a big limit of being a book about war and deception. Modern markets are rarely a true battlefield. And can provide a true and valuable tool for analysing the current scenario and develop a Strategy. What is interesting is the focus that this approach gives on the internal analysis of existing capabilities. A winning element.

Hambrick and Fredrickson’s Strategy Diamond

The Strategy Diamond is an attempt to explain what strategy truly means providing a framework that lists all components of a strategy. According to this model, a strategy consists of five essential parts that together should form a unified whole: Arenas, Vehicles, Differentiators, Staging and Economic Logic. For each element, concrete and deliberate choices have to be made on what to do and more importantly, what NOT to do. (Hambrick and Fredrickson, 2001)

Decisions made within one element should reinforce and match decisions made in the other aspects of the model, thus ensuring consistency. Only that way, companies can achieve a sound and sustainable strategy.

This model stresses, therefore, the concept of Strategy as a system of Choice. Read more about one concrete example applied to Ikea.

The Value Disciplines Framework

The Value Disciplines Framework builds upon the basic concepts of Porter’s Generic Strategies. In their book ‘The Discipline of Market Leaders‘ M. Treacy and F. Wiersema propose three value disciplines from which companies can choose from to become a market leader, by creating a real focus:

- Product Leadership (the best and most innovative product offering),

- Operational Excellence (the cheapest products through a cost-efficient production process), and

- Customer Intimacy (fantastic customer service and customer relationship management).

The strategy, therefore, becomes the way you choose and balance the way to operate in each value discipline. This is one of the first models that creates a real Customer Focus, as the strategy becomes the right way to embed customer choice as a source of strategy. This framework involves the fact that the company will also need to choose an Operating Model that is consistent with the chosen Value Discipline.

Scenario Planning

Developed originally by military organisation RAND in the US, it became famous in business circles from work done by Shell and its organisation (Schwartz, 1991), the basic idea of Scenario Planning is that it is not possible to define precisely what the future will be. Still, rather it is essential to identify the macro-trends and define possible alternative scenarios that these might determine. Thanks to the model, Shell was the only company that was able to resist the first petrol price shock in the early Seventies.

The figure represents a typical illustration of a scenario based on two dimensions. This is the purest form and looks typically at the inter-dependencies of two macro trends, chosen for their possible impact on the organisation, rated by intensity levels.

For example, let’s assume I’m an oil company, and I envision that the two fundamental dimensions that can affect my business are environmental regulations (that I could depict on the vertical axis) and discovery of new reserves (applied to the horizontal axis). I could have four quadrants representing the interaction of these two driving forces. Quadrant A could be a situation where no new reserves are found, and environmental regulations become stricter. This scenario would most probably entail higher prices. Quadrant B would be instead associated to further reserves found with more stringent regulations. This could mean a situation of higher costs, but not necessarily higher revenues. Quadrant C would be a situation where no new reserves are found, but also no new environmental regulations are set. This would probably resemble more nearly to the current status quo. Quadrant D would be a situation where further reserves are found, and no additional environmental regulations are put in place, probably a best-case scenario.

It’s easy to understand that different strategic options need to be evaluated for each of the scenarios. Usually, there is a storytelling component that is used to develop each scenario so that everybody in the organisation can understand them. Usually, the interaction of the two forces has many ripple effects, and these need to be evaluated.

Working with Scenarios is often associated with Strategic Thinking like a real organisational capability, which essentially means being flexible and agile to cope with different versions of reality that can appear. In a VUCA world, this capability is even more critical.

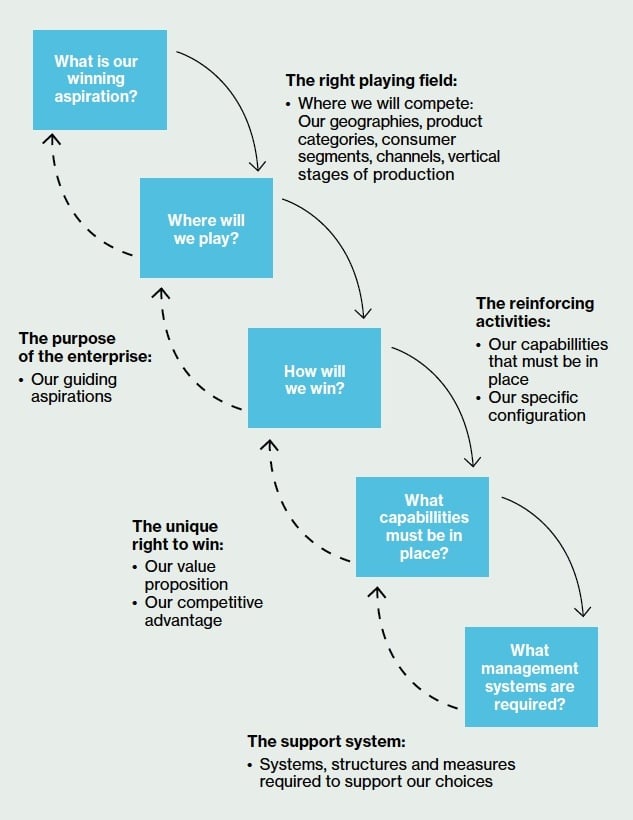

Where to Play – How to Win

This Strategy Definition Model descends from the Procter & Gamble experience and is illustrated in the book Playing to Win: How Strategy Really Works by A.G Lafley and Roger L. Martin (2013). The authors lay a straightforward model to define a strategy through several choices, illustrated by five simple questions.

- What is our winning aspiration? Which mostly looks at the purpose of the organisation, or instead as a definition of “winning”.

- Where will we play? This is about defining the focus of the strategy and the organisation, in terms of a market niche.

- How will we win? Cost Leadership and Differentiation are the two typical strategies, but how these are combined can be unique to the way the company will act.

- What capabilities must be in place? This is the link to the internal resources of the organisation and should look at the capabilities the company has and the ones it needs to develop.

- Feasible: Something, your organisation, could do, even if that means investing in creating it

- Distinctive: Having superior WTP and HTW choices isn’t enough if the activity system is the same. Your competitor could just shift over.

- Defensible: Even if your competitor doesn’t have the same core capabilities, could they develop them quickly.

- What management systems are required? This is the link with the Operating Model of the organisation and looks at how the organisation needs to be set up to execute its strategy.

This model is used across the globe by many companies, as it allows a focused cascading of the strategy as well as a thorough consistency in the development of the strategy itself. Also, in the book, the authors identify a way to determine the strategic choices through several tools that focus on Industry, Customer Value and Relative Position.

Overall this creates a strong framework for the definition of a Strategy that focuses on consistency and cascading.

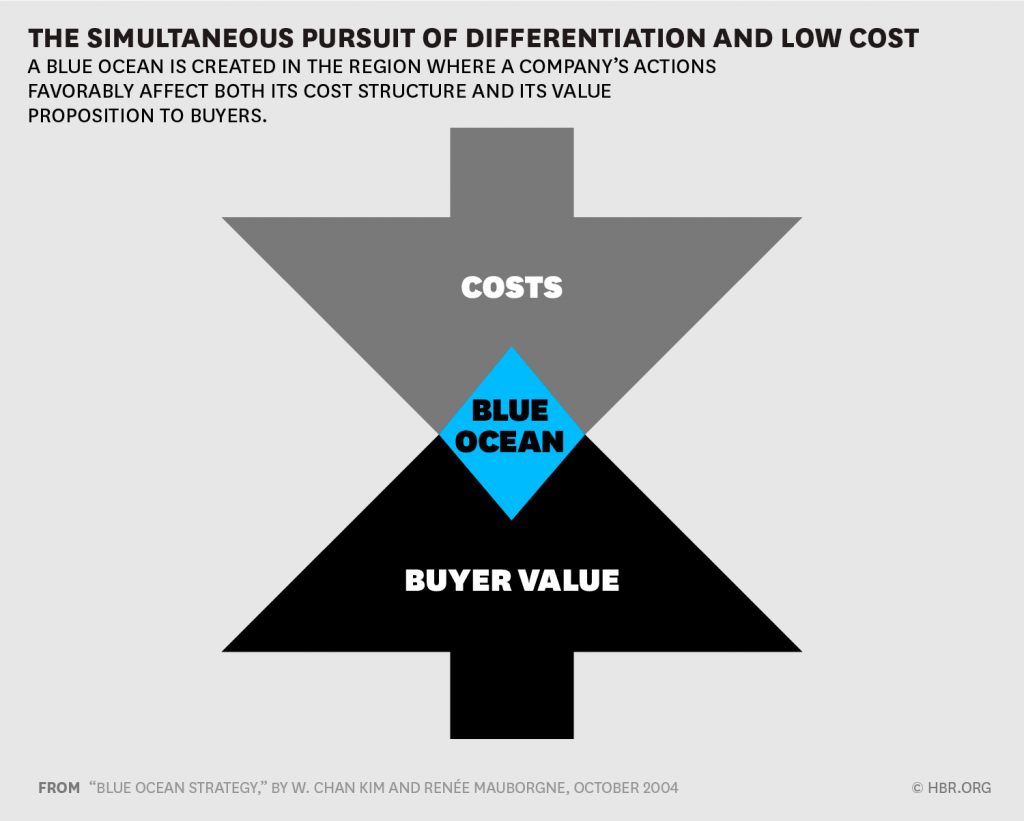

Blue Ocean Strategy

It is a concept that W. Chan Kim and Renée Mauborgne developed in a 2004 article and subsequent book by the same title: Blue Ocean Strategy.

Imagine you are the only fisherman in a vast ocean full of fish. How successful will you be with day of fishing? Unequalled for sure…

Blue Ocean Strategy is as simple as that: sailing the large ocean in a competition-free market. Because of your unique competitive position, you can maximize profits until others see the opportunity and enter the market. As such, you can pursue both differentiation and low-cost strategies (partially contradicting Porter’s view of General Strategies).

Getting into a blue ocean is, however easier said than done. At the basis of a Blue Ocean Strategy (as opposed to what the authors define as Red Ocean Strategy), there’s a heavy focus on innovation and constant change. Bringing up an entirely new product is not sufficient because the competitive advantage doesn’t last forever. Each Blue Ocean is destined to become a Red Ocean. Here you can still compete, using the standard practices already suggested by Porter.

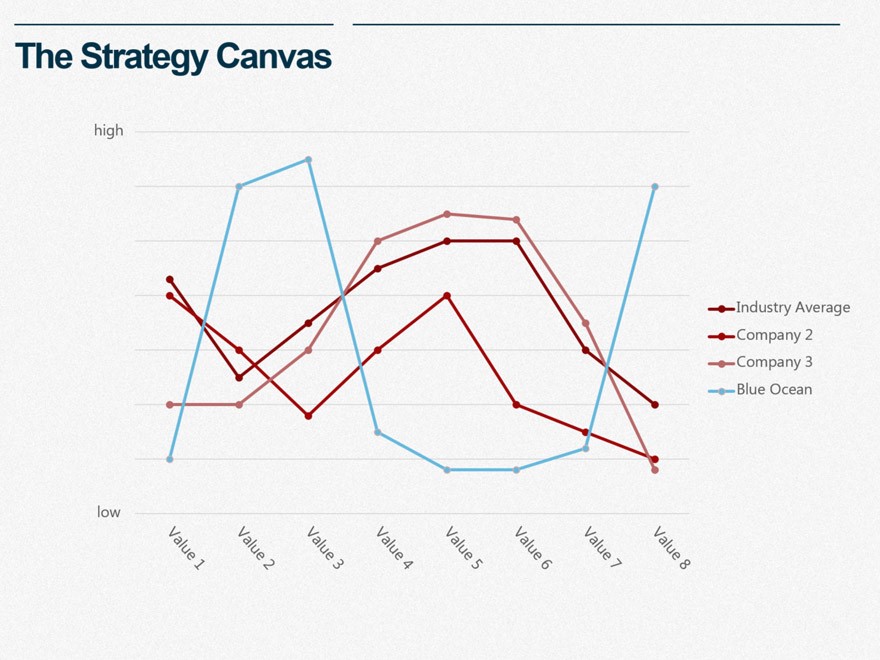

Blue Ocean Strategy is based on a wide range of strategic frameworks allowing you to find how to create value through innovation. “Strategy Canvas” is one of the most important ones because this tool helps you differentiate a product from your competition. The Canvas helps you by assessing what is valuable for your customers, where the industry is investing and checking if there are gap areas that your competitors are ignoring.

This approach and the related toolkit have become pretty mainstream in these years, especially after the book has become a bestseller. Thanks to technology, many companies have been able to build their niche markets, developing overwhelming success.

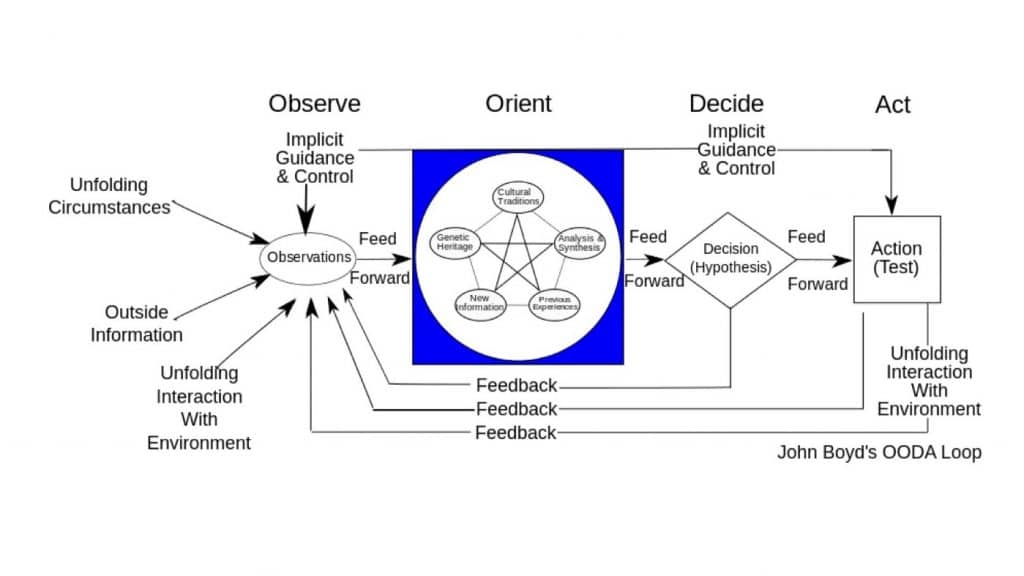

OODA Decision Framework

The OODA Decision Framework or OODA Decision Loop is the acronym of a four steps process: observe–orient–decide–act (Boyd, 1976), developed by military strategist and United States Air Force Colonel John Boyd.

This model is currently used in many domains, including strategy (Wikipedia Contributors, 2019a). The most interesting aspect is the second element: the Orient part. Our ability to orientate depends upon our previous experience, cultural heritage and genetic disposition to the events in question. In terms of an organisation, its genetic disposition is akin to the doctrine and practices it has. This essentially means that the Strategy of an Organisation will always be impacted by the history of the organisation itself. An element of profound implications (Wardley, 2018).

The second relevant element of this model is the continuous multiple feedback loop it entails. A Plan therefore is never a straight line of actions, but rather a constant adaptation based on the feedback obtained. As such, compared to the typical Plan Do Check Act model (which essentially governs many strategy plans), this approach effectively moves away from a typical planning pattern, allowing for exploration and innovation.

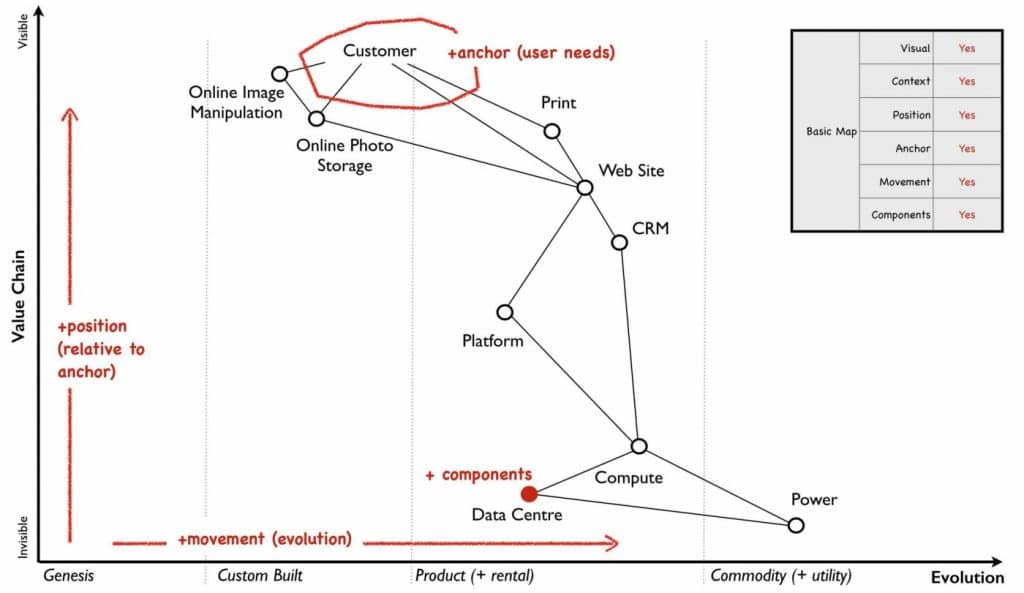

Wardley maps

Invented by Simon Wardley, these are maps of the structure of a business or service, mapping the components needed to provide value to a user. Wardley has written an extensive guide on his methodology and publicly available on Medium. After accidentally discovering this tool, I have decided to list it as part of this article, for the extremely useful potential of this tool.

The model derives from a unique approach that Wardley developed on Strategy (partially derived from Sun Tzu’s Theory, but updated to modern reality). The Map attempts to visualise all components that form a Strategy. The first one is the Anchor, seen as the Customer of User of the organisation, interpreted through its needs. Context is provided by illustrating the entire number of Components that are relevant to deliver the necessary value to the customer. These are positioned on a two-axis diagram in terms of Position (based on the relative perceived value to the Customer) and of Movement (i.e. the relative evolution stage on which the component sits). The tool allows the visualisation an entire customer journey, but focusing on a multi-factor positioning of each component, thus allowing to make strategic decisions more easily, according to its proponent. What is interesting about the Map is that they are dynamic: the “movement” element pushes each component towards the right due to competition. I will dedicate more time in analysing this methodology in a specific article in the future.

How to use Strategy Models

With few exceptions, there’s not a model that can genuinely allow an organisation to develop a consistent and sound strategy fully. Multiple tools are often needed to be used in conjunction, to ensure that a view is built on the external market, internal capabilities, portfolio and priorities.

It is therefore difficult to assess which tool is best above all the others.

My suggestion is, therefore, to simply ensure we can evaluate the current strategy of a company, and ensure that, if there are gaps, these are filled with the best available tool. An excellent way to evaluate a strategy comes from another management literature classic, a 1962 article by Seymour Tilles titled How to Evaluate Corporate Strategy. He lists six criteria:

- Internal consistency.

- Consistency with the environment.

- Appropriateness in the light of available resources.

- Satisfactory degree of risk.

- Appropriate time horizon.

- Workability.

If all of these criteria are met, you have a strategy that is right for you. This is as much as can be asked. There is no such thing as a good strategy in any absolute, objective sense. (Tilles, 1963)

I have already written about Consistency and the fact that it is an essential factor, but needs to be considered with some limits. However, these six factors hold to the progress of time, even if some of its definitions needed to be adapted over time.

Conclusion

With this article, I complete the first pass of views of the four foundation components of Organisation Design: Business Model, Strategy, Operating Model and Organisation Model. It is tough to identify models and frameworks that satisfy the taxonomy I have suggested to use, as there are often overlapping edges. Strategy is probably the topic where HR has traditionally been less involved. One of the peculiarities about this area is that in many organisations, this is not merely an activity that is carried more or less periodically but is also a department within the organisation.

One of the problems that I often see in many companies is that there is an artificially built cleavage between Strategy and Execution. But, as we have seen, Strategy is precisely the definition of how we execute, which is why it is a principal activity for managers. Many of the authors we have encountered have typically expressed this point of view. Strategy is not and should not be a discipline for the few, but rather a toolset for all managers, to be applied within their span of influence.

Too often, many managers (and consultants) seem to put a higher stake on the development of a Strategy. But good Strategy necessitates proper Execution. This is the core of what an organisation stands for.

Disciplines and tools like Organisation Design and Governance are vital components of this, together with culture, leadership and the correct balance of skills. All of this is Execution.

The key in today’s world is ensuring a level of Deliberate Consistency that is much higher than before, which is why glueing mechanisms like Passion and Motivation, or being Deliberately Developmental become the valid winning arguments.

What’s funny is that we end up labelling all these elements as part of a rebel movement. The real rebellion seemingly being into linking successful strategies with excellent Execution.

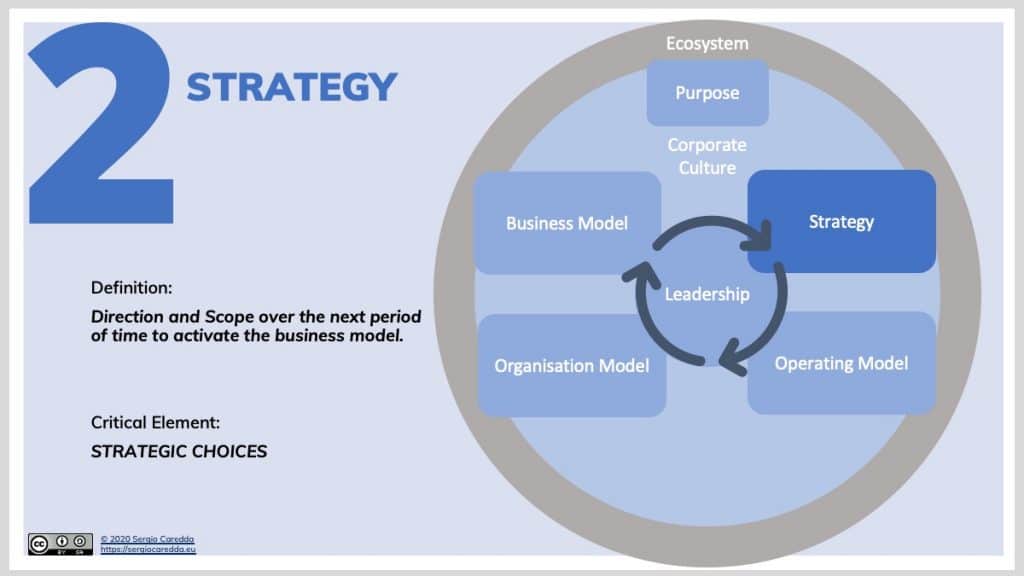

Strategy within the Organisation Evolution Framework

This is the link with the Visual Framework that I have built and that allows visualising all essential building blocks of Organisation Design: the Organisation Evolution Framework. Here below the representation of Strategy with its definition and the Critical Element that derives from it: Strategic Priorities.

Within this framework, my definition of Strategy is the Direction and Scope over the next period of time to activate the business model.

Introducing the Organisation Evolution Framework

Visual representation of Organisation Design building blocks and their dynamic relationships.

Now released in Version 2, open for feedback.

Also, this article is open for feedback, integration and corrections. Please use the comment section below. I’m sure I missed many tools on this list.

Cover Photo by Matthew Henry on Unsplash