The Ultimate Quest for the Meaning of Work cannot avoid looking into the depths of our History. In this first post of the series, I will try to give a quick overview of how the concept of Work has evolved, particularly with the surrounding forces behind it, including the overall society. Most books that I have accessed on this content, often have a socialist point of view, thus interpreting Work as an exploitation of a class over another. Although this aspect repeated itself over time in History, it is, however, one of the possible readings we can have in the development of society.

This is why I have decided not to use most of that literature, and concentrate really on a few encyclopedical references on the History of humankind and its relationship with Work. It will serve as an excellent introduction to the content of the next post, where I will try to extrapolate the Discourses of Work through time.

A Brief History of Work

Thinking about Work and its meanings is deeply rooted in Human History. But even before, we can trace some elements of what we can define as “work” in primate populations. The capability for some apes to produce tools is probably the nearest concept that we can find to that of Work. With the appearance of the first hominids, Work starts taking a massive impact in their differentiation from other animal species. The use of art to embellish tools is not just the sign of maturing human culture—it also signifies a changed relationship between people and objects, embodying several critical aspects of the meaning of Work: one is aesthetic sensibility and symbolism. Another is reverence and metaphysical belief systems. (Nicholson, 2010). Work was, however, a mainly individual activity, or the result of collaborative practices (such as in hunting).

Around 10 000 years ago, the proto-agricultural practices of our intelligent ancestors developed into the first fixed agrarian settlements. The design of Work changed radically at this point. Labour on the land became organised around collective tasks linked with the cycles of the seasons—agriculture and animal husbandry—and around tasks associated with the establishment, maintenance, and growth of fixed settlements. The ownership of Lands and of the Produce of the earth became the first element that created human hierarchies and the concepts of ranks in some cultures. It also made, for the first time, a differentiation between people that were working, and those that weren’t (chiefs, priests and so on).

Different Meanings for Different Societies

As societies started to develop, so did also the idea of Work. A good sample can be found in the Bible, where we can trace three distinctive meanings of Work. (Gagnier and Dupré, 1995):

- As an achievement, with the six days spent on creation. (“And God blessed the seventh day, and sanctified it: because that in it he had rested from all his work” Genesis 2:3).

- As an alternative to leisure and rest, when God rests on the seventh day (same verse).

- As a burden and punishment, when Adam is sent away from Garden Eden, he is condemned to work. (“In the sweat of thy face shalt thou eat bread, till thou return to the ground “, Genesis 3:19)

This concept of punishment is still traceable today in the roots of the word labour, shared by “work” as well as by the process of childbirth (which was the other “punishment” given by God in the Genesis, specifically to Eve). In many cultures, the concept of Work as Punishment continued to evolve. We can trace this specifically in ancient Greece and Rome, even if there was a definite distinction between Agricultural Work (its strong link with nature created a positive philosophical spirit behind, symbolised by the beauty of Arcadia), as opposed to the rest of “manual work” which was considered overall “negative”.

n Roman time, mainly, we see the creation of a hierarchy of types of Work. First of all, the majority of physical Work was done by slaves. The Roman Economy was profoundly established on Labour as a genuine Production Factor, a factor that was possessed, sold, exchanged.

A second layer was that of the “physical” activities done by citizens, which were usually collectively identified as Negotium. This included all commercial activities (again, the root of the term still echoes in today’s negotiation), but also warfare: an essential element in the lives of many for a significant part of History. For many decades a robust debate involved many Latin intellectuals, on the distinction between Negotium and Otium, which was the complex of activities which constituted the positive side of human activities. Cicero wrote at length about it, celebrating the man that would engage in activities such as the political oratory, the composition of poetry, music and so on. The core idea between the distinction of Otium and Negotium was that the majority of people (notably including women and slaves) should engage in physical Work so that the few “elite” could concentrate in advancing humanity through otium and reflection.

Modern Work Design

With the advent of Christianity, we see some new developments. Cloisters became the centre of many different types of Work, and work itself becomes part of the believer journey toward redemption. A new meaning starts to develop, that of Work as a way to achieve personal sense. The monasteries were arguably the first genuinely modern organisations, in terms of integrated management and production systems (Nicholson, 2010). Still, some areas of Work were considered devilish, and this distinction will persist, and this will continue to characterise a big part of the way Christianity saw Work, up until Luther’s reforms. For him, still, banking, credit, trade were considered as part of the ‘kingdom of darkness’ (Gagnier and Dupré, 1995). Only Calvinism went beyond the stigmata on some types of Work, bringing to the later identification of Protestantism as the foundation of capitalism (Weber, 1982).

With the re-development of cities in Middle Age, there is, however, an important phenomenon that starts shaping the world of Work. The first is the distinction between Arts and Crafts, an element that we can trace, for example, around the building of the Great Cathedrals in Europe. But Medieval Time starts also developing an essential movement of Workmanship. Young pupils would go and work in a workshop, learning from the Master as Apprentices in the first structured mentoring approaches. Work becomes a mission, and the output becomes a soul-fulfilling endeavour, often filled with a religious zeal. Crafts got organised into Guilds, to provide regulations, but also to control the offer of specific Work. In some cities Guilds slowly got also hold of the political power, and some of the guilds gradually transformed into actors that contributed at the shaping of modern society (think about the Freemasons). (Dupré, 1996)

With the Renaissance, Arts started flourishing together with a new set of scientific discoveries. Commerce and trade developed as well. Although the critiques still exerted from the official Catholic views, we see also Trade and Banking flourishing, creating the first forms of modern enterprises. And it is in this framework that several of the tools that still influence today’s Work have been made, such as the double-entry accounting system. It is however also the moment where the first examples of specialisation in Work get noticed, for example in some large mining compounds in Germany, where the first recorded examples of a modern hierarchical organisation are described (Kranzberg and Hannan, 2017).

The advent of the different phases of the Industrial Revolutions was accompanied by social rejection of the last forms of slavery as a form of control of labour. However, the development of sweatshops did not change much in the living standards of many workers, compared to the Work in plantations, for example. The same Revolutions, however, created the need for the new modern enterprise to get organised around the newly coined Factory, making for the first time a distinction between “manual” and “intellectual” Work within these companies. A difference that we still carry on today: that between White Collars and Blue Collars. It is in this scenario that the concept of the work as a voluntary contracted position becomes a meaningful entity (Nicholson, 2010). It is at this time that we can trace the first scientific study of work design which “started with the work of Adam Smith, who described in his book The Wealth of Nations how the division of labour could increase productivity” (Van den Broeck and Parker, 2017).

The Birth of the Job.

However, it is in the nineteenth century within the ranks of the military first, and the offices needed to manage large empires and kingdoms, that a new concept starts appearing on the scene. The idea of Job. It’s not easy to find an exact moment when Work became a job, but we can trace in Max Weber and his definition of Bureaucracy one of the first descriptions of what its key characteristics are. The first one is a clear definition of roles and responsibilities, derived from a division of labour that is functional. The second is a clear distinction between personal and “office” property (up until that moment, most workers would provide their tools). The third is a clear set of rules that manage the organisation, through a hierarchical principle. Fourth is the fact that organisation can become impersonal: treating individuals based on their qualifications rather than on their origins or class, for example.

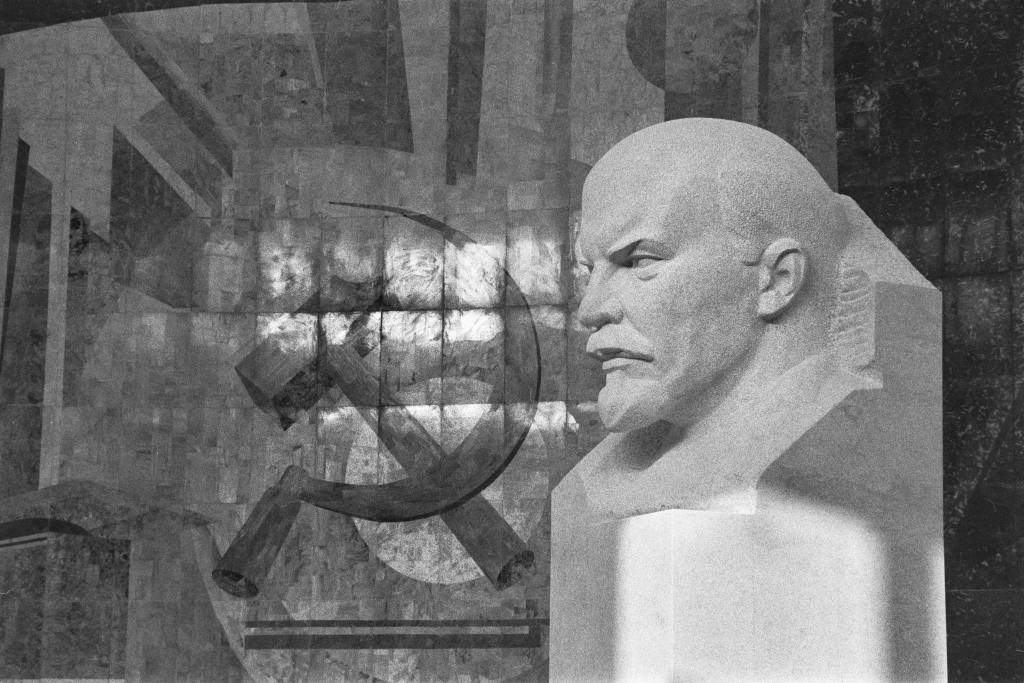

These principles are at the core of the concept of Work in modern society. Taylor brought the ideas to the extreme, expanding these from bureaucracy also in technocratic production units. The specialisation of Work becomes the realm of a new form of engineering (Kranzberg and Hannan, 2017). Jobs are designed from the top as part of an unrelenting quest for efficiency. The worker does not possess the results of his Work anymore. They have now become employees in a new type of relationship (Employer-to-employee) that will define the central discourse of work for the contemporary era, epitomised by the work of Karl Marx and the Socialism after him.

The long tail of Taylor’s approach reverberates through the two World Wars. In most of the Western World, the Fifties are labelled as the age of security. Jobs are celebrated as the apex of efficiency, allowing for the rapid growth of wealth in many countries, while crafts and agriculture jobs shrink considerably. Leisure becomes an important economic factor, as new Work develops to fill the increasing spare time a generation of the employer now has.

A World of Insecurity

The Seventies and Eighties, however, bring back insecurity in the world of Work. Efficiency looks at a more global scale, and the first large waves of automation and outsourcing create new frictions.

Individual Passion, Motivation, Engagement are recovered as concepts of a humanistic ideal, to improve competitiveness and profits. When these are not reached, the not-so-passionate employee is rewarded with downsizing, restructuring, flexibility.

These tensions are increased by the dissolution of the Communist Block in Europe, and slowly around the Globe. With the sudden decay of the largest ideology that celebrated the primacy of Work, the sole alternative reading seemed that of the Capitalist view of a world of work dominated by a relentless pursuit of profit.

In the Nineties, we got an apex where more employees around the world had unstable or part-time working situations than ever before. At the same time, masses of people start an increasing flow of economic migration towards the more affluent countries, in search of better Work opportunities. A new stratification builds up, with an increased gap between the richer and the poorer. Work is not anymore the domain of stability, but instead becomes a source of anxiety for most.

Increases in work-related illnesses mark the fact that something is broken in the world of Work intended as a safety tool for individuals’ lives.

The Knowledge Worker Revolution

Some seeds of a new version of the concept of Work seem to establish themselves. The humanistic images we have already seen, start to find fertile soil in a new kind of industry, dominated by software development and technological invention. Silicon Valley is not just a physical location, but an ambition for many, where modern meanings of the concept of Work are affirming.

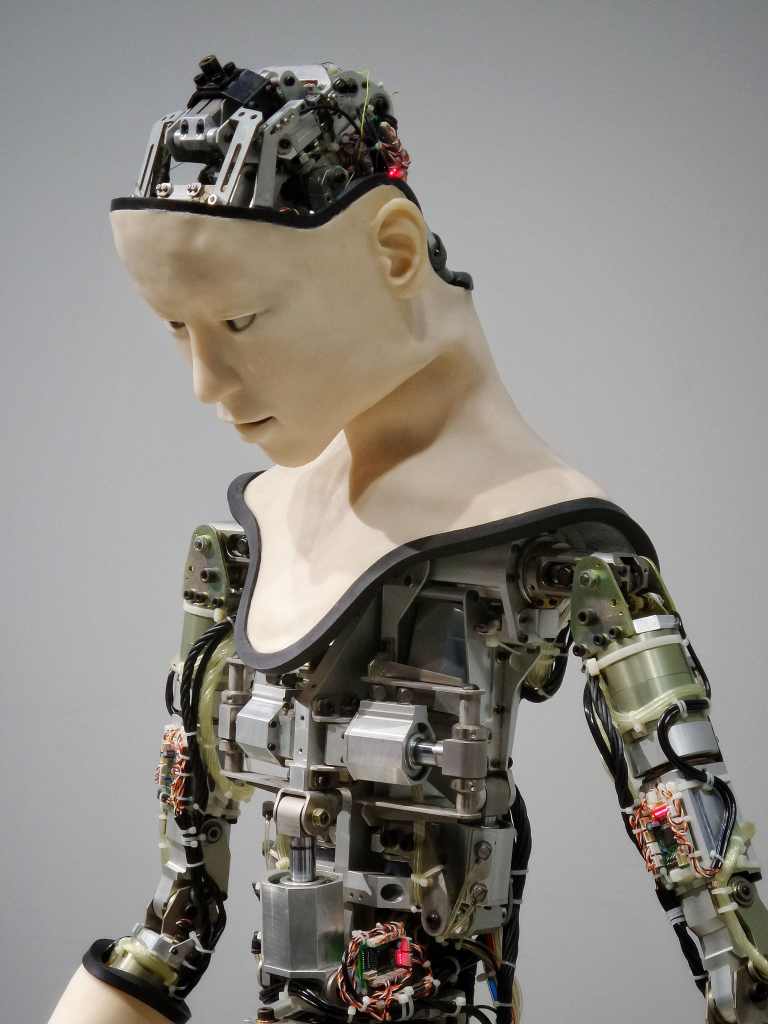

This new wave of self-entrepreneurialism, self-expression, personal creativity has flown across the world of Work. The concept of “Knowledge Worker” appears and with it the realisation that efficiency-seeking policies have firm limits. Creativity, Innovation, Knowledge creation cannot be bound to reductionist optimised processes. We need alternative views.

The sheer size of the global players in technology, start contaminating the agenda of more traditional industries. Concepts such as work-life balance, diversity and inclusion, wellbeing start to connotate an entirely different approach that some organisation take on the meaning of work.

A few pioneering actors also seek to disrupt the core element of the more traditional work narrative, focusing directly at the core of the Employer-Employee relationship. Uber, Lyft, Foodora, JustEat and many more build platforms that can link in the work of individuals without formal relationships, creating a wave of gig workers across the globe.

Many react, yet the fact that global firms can work with thousands of different work arrangements is a reality that can only be acknowledged. Other companies challenge another foundational assumption of traditional work: that of the workplace. Gitlab and Basecamp are just some examples of companies that are entirely virtual entities, acting through a globally distributed workforce.

The recent Covid-19 pandemics has accelerated these trends but also exposes to the world that not all organisations are mature enough to sustain this change, and current legislation still limits the way Work is intended.

All this reinforces the idea that a new discourse around work is forming, and that we need to think in terms of the need to Reinvent Work profoundly.

This article is the second in a series of seven posts on the Meaning of Work. Please feel free to add any feedback to this article in the comment section.

Cover Photo by Quino Al on Unsplash

Reference List

Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety (2002). Job Design. [online] Ccohs.ca. Available at: https://www.ccohs.ca/oshanswers/hsprograms/job_design.html [Accessed 3 Oct. 2020].

Dupré, J. (1996). A Brief History of Work. Journal of Economic Issues, 30(2), pp.553–559.

Enciclopaedia Britannica (2020). work | Definition, History, & Examples | Britannica. In: Encyclopædia Britannica. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/work-economics.

Gagnier, R. and Dupré, J. (1995). On work and idleness. Feminist Economics, 1(3), pp.96–109.

Gervais, R.L. (2010). Definition of work/job design: OSHwiki. [online] Oshwiki.eu. Available at: https://oshwiki.eu/wiki/Definition_of_work/job_design [Accessed 3 Oct. 2020].

Haworth, J.T. and Anthony James Veal (2004). Work and leisure. London ; New York: Routledge.

Joyce, P. (1989). The Historical Meanings of Work. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kranzberg, M. and Hannan, M.T. (2017). History of the organization of work. In: Encyclopædia Britannica. [online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/topic/history-of-work-organization-648000.

Nicholson, N. (2010). The design of work-an evolutionary perspective. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 31(2–3), pp.422–431.

Van den Broeck, A. and Parker, S.K. (2017). Job and Work Design. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology. [online] Available at: https://oxfordre.com/psychology/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.001.0001/acrefore-9780190236557-e-15 [Accessed 3 Oct. 2020].

Weber, M. and Johannes Winckelmann (1982). Die protestantische Ethik. Gütersloh: Gütersloher Verlagshaus.

[…] what has to come to the role of work. In many ways, this book has added many confirmations to the Brief History of Work article that I wrote, and more content in general for the Meaning of Work series. It helps once […]

really enjoying your posts, it’s time to reinvent work. WFH was a revaluation for many, creating work life balance especially for women, that made working more enjoyable. It could have helped increase female participation had it been embraced but Unfortunately the human experience is not factored in as organisations now demand return to offices, aided by governments pushing economic agendas. Demanding commutes to sit at desks for hours for work is stepping backwards, at least hybrid models could be promoted.

[…] Caredda, S. (2020). Part 1: A Brief History of Work | Sergio Caredda. Sergio Caredda. Retrieved 10 February 2022, from https://sergiocaredda.eu/people/future-of-work/part-1-a-brief-history-of-work/. […]

[…] who balk at the idea of people not working to earn their living, it’s worth remembering that the history of work is hardly consistent with how we define it today. Indeed, the notion that we should “earn our […]

[…] who balk at the idea of people not working to earn their living, it’s worth remembering that the history of work is hardly consistent with how we define it today. Indeed, the notion that we should “earn our […]